What's on CRE Owners' Minds—Smart Building Maturity Moves from NexusCon 2025

Office landlords are stuck in a paradox. Tenants expect modern buildings that just work—connected, secure, efficient. Investors question why you're spending capital on technology infrastructure that wasn't in the original asset plan. And meanwhile, your buildings vary wildly—Class A downtown towers next to aging suburban assets, each with different ownership structures and joint ventures—making any standardized approach nearly impossible.

The question isn't whether to invest in smart building technology anymore. The question is: how do you actually do this across a real portfolio without burning credibility, blowing budgets, or creating a dependency on a single expert who becomes a crutch for the entire organization?

At NexusCon's Building Owner PreCon, three CRE leaders who've been running smart building programs for years gathered to talk about what's actually working. Thano Lambrinos, VP of Digital Buildings at QuadReal Property Group, Nada Sutic, Director of Sustainability, Innovation & National Programs at Epic Investment Services, and Grigor Hadjiev, Head of Real Estate Development Europe & Global Head of Innovation at PIMCO Prime Real Estate, all manage office properties as landlords—not owner-occupiers with direct control over operations.

They didn't talk about innovation or tenant experience apps. They talked about networks, cybersecurity, and construction fights. They talked about how to stop justifying every technology investment with a spreadsheet. And they made the case that the real maturity move is treating smart building infrastructure like elevators—expected, essential, and no longer requiring exhaustive ROI justification.

Their programs have been running for years—some as long as seven and a half—and they've moved past pilots into portfolio-wide implementation. What they've learned offers a clearer picture of what maturity looks like when you're protecting asset value across diverse portfolios.

The Landlord Reality Check: Back to Fundamentals

Here's what didn't work: chasing tenant experience apps and return-to-office features while ignoring the infrastructure underneath.

When Nada Sutic joined Epic Investment Services in 2022, the market was still excited about bells and whistles for bringing people back to the office. That enthusiasm evaporated fast. What remained was a harder question: how do you manage risk across a portfolio where buildings range from 800,000-square-foot downtown towers to 50,000-square-foot suburban B and C class assets?

The answer wasn't sexy. Base building networks. Cybersecurity protocols. Operational visibility. As Sutic put it: "I need to have a base building network and I need to have some cyber security in place".

Getting budgets approved hit a wall. Property managers didn't know how to sell these investments to the asset managers who approve budgets. Epic's solution was practical: go client by client, sit down with asset management teams, and stop talking about "smart buildings." Frame it as risk management, tenant experience, enhanced operations, and cost management. The message was realistic: "You don't have to do everything right now. We'd love it if you did, but understand that there are risks if you don't, and that's okay. We just need to be able to manage that and be aware".

Budgets started getting approved. Epic now has base building networks with cybersecurity protections across the portfolio. Progress came through education and reasonable conversations, not better technology.

Beyond ROI: When Smart Tech Becomes the New Elevator

Here's the counterintuitive move that unlocked these programs: they stopped trying to prove ROI on every technology investment.

This goes against everything the industry preaches. Everyone assumes you need better KPIs and more rigorous measurement. But spending months calculating business cases for smart building investments was, as one leader put it, just burning time on metrics that ultimately didn't matter.

The problem with ROI calculations is they treat technology like a discretionary expense rather than infrastructure. But real estate investment decisions don't actually work that way. They're based on conviction. You need to know who the decision maker is and what will convince them—a coffee conversation, a small demonstration, making their life easier—not a 47-page financial model.

Thano Lambrinos was blunt about this. When you present business cases, almost no one goes back to check whether every projected number was hit. But everyone intrinsically knows that integrating building systems, improving visibility into data, centralizing operations, and streamlining construction creates value. As Lambrinos put it: "It's kind of silly to think that there's no value in integrating a whole bunch of building systems and getting better visibility and data. There's no value in centralizing the way that we operate. There's no value in streamlining construction. That's just really dumb."

His advice? Don't be afraid to make things a little fuzzy. Investment committee presentations contain plenty of hopeful projections—technology programs should do the same to get moving. There are real returns to point to around energy savings, construction efficiency, and maintenance optimization. It just takes time.

Sutic drew a parallel to sustainability's journey. Fifteen years ago, the question was whether green buildings created value. The answer was "we're pretty sure". Eventually, solid studies using real lease data proved that certified green buildings commanded more rent. The value existed before it could be precisely measured.

Technology follows the same pattern. Can you build a 30-story building without elevators? Sure, but you don't. Elevators are expensive. Nobody demands an ROI calculation before installing them because they're infrastructure, not amenities.

That's the shift. Smart building systems are moving into that same category—expected components of how modern buildings function, not optional upgrades requiring exhaustive justification. When landlords make that mental shift, technology budgets move from discretionary innovation funds to baseline capital planning.

Smart as Standard: Table Stakes for Prime Office Space

Once technology becomes infrastructure, the marketing conversation changes. Don't market technology as a standalone feature. Lambrinos described River South, a QuadReal building in Austin, Texas—the first development south of the river in a market flooded with vacant office space. The building hit 100% occupancy not because of its technology alone, but because it combined beautiful design, good amenitization, an amazing sustainability program, and technology into a compelling whole.

Talk about outcomes rather than features. Don't market sensors—explain what those sensors accomplish. But the conversation is also evolving beyond marketing. Prime buildings now have automated energy adjustment based on temperature and occupancy. They have digital security protections. The more the industry matures, the more these capabilities are presented as integral to prime product rather than as something separate.

Lambrinos made the comparison explicit: "Show me the return on the artwork that you spend $200,000 on in the lobby. Show me the return on the marble that you put in the bathrooms". Nobody asks those questions because lobby finishes are understood as part of what makes a building competitive. Technology infrastructure is moving into the same category.

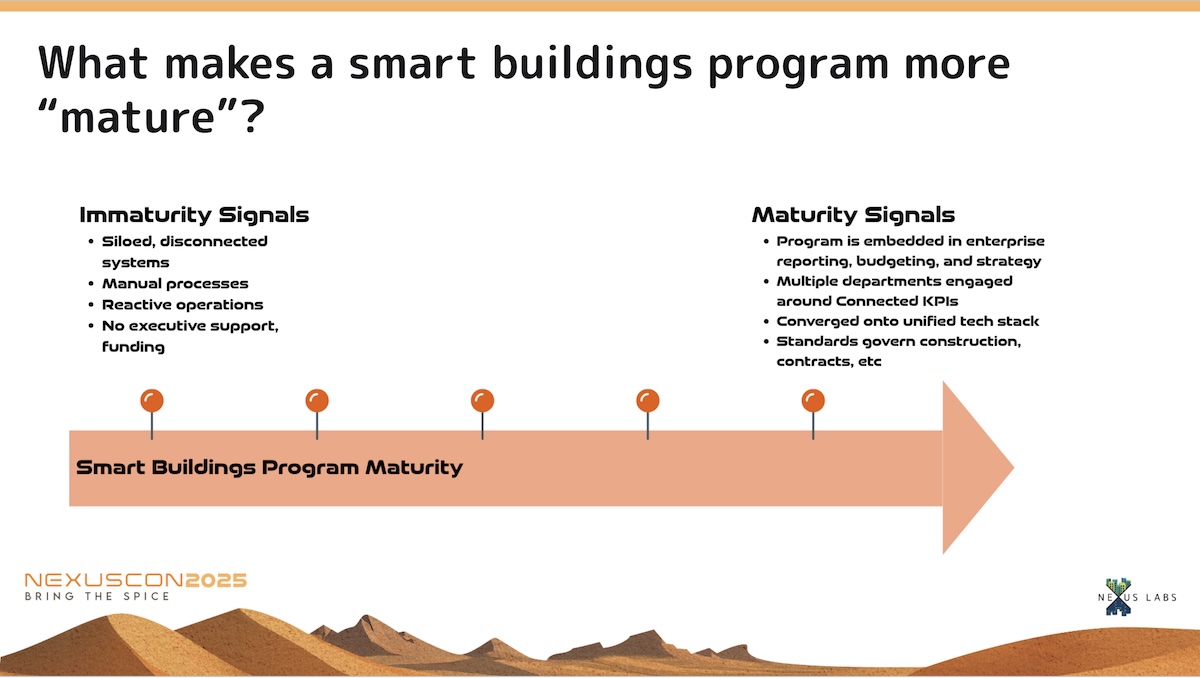

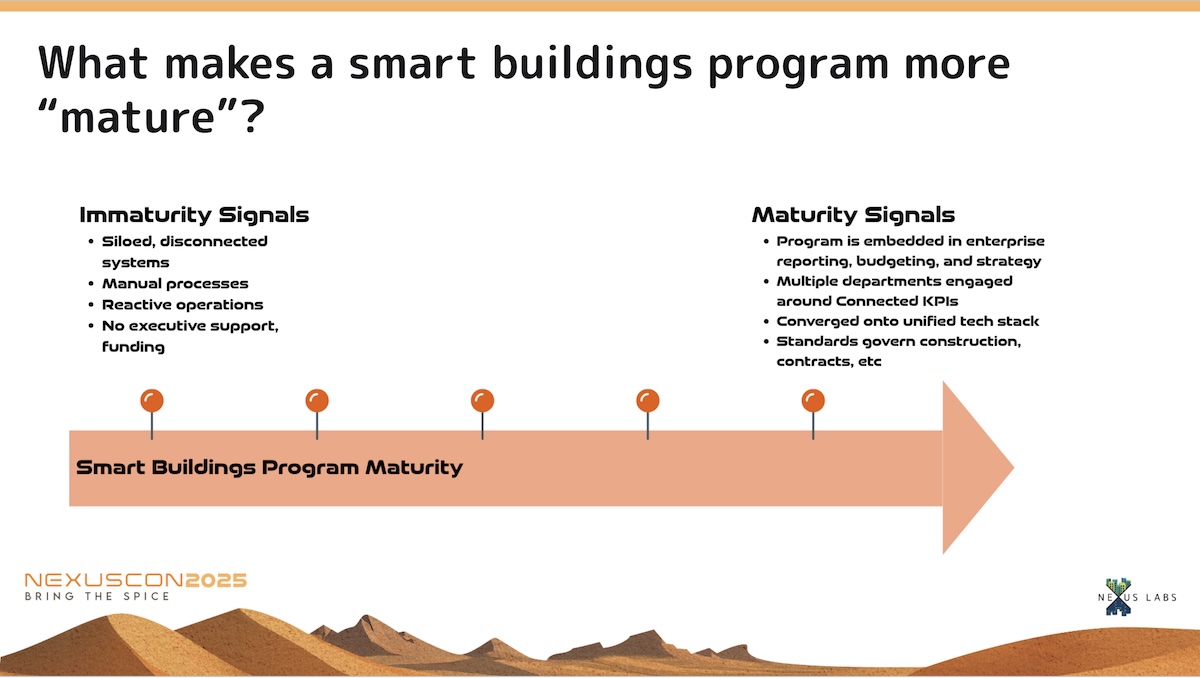

Maturity Moves: Building Programs that Stick

So how do you move from startup phase to portfolio-wide operation? It's not about technology choices—it's about organizational muscle.

Lambrinos outlined QuadReal's progression: first came simple connectivity and visibility into what systems existed and where. Next was integrating those connected systems. In parallel, they built their own tenant experience environment rather than paying premium prices for vendor solutions. Then they expanded scope to include not just technology but every building system except the concrete, glass, finishes, and roof.

The key to success was having control or influence over scope across the board, because trying to layer technology over systems you don't control is "kind of a lost cause".

One specific move unlocked broader deployment: convincing asset management to put a network into a single building. That success enabled rolling out a massive portfolio-wide program. Small wins open doors to bigger moves.

For PIMCO Prime Real Estate's building signature initiative, the path involved creating a blueprint covering multiple areas simultaneously: collecting environmental data through smart meters, implementing comfort and occupancy measurement, establishing a central data lake for decision making, and building cybersecurity protections. Over five years, they've connected over 1 million square meters of space.

Maturity comes through repeatable, scaled decisions—not one-off pilots. It requires executive alignment on clear outcomes early. It demands proving value through small wins. It prioritizes connectivity and integration before chasing analytics or AI applications.

Overcoming Industry Friction

Even well-funded programs with executive support crash into construction teams and vendor lock-in.

When asked about getting construction teams to buy in, the answer was simple: "fight". Construction teams don't want to change how they've operated for 30 years. The solution required creating standard specifications, embedding digital building teams in projects, taking over scope, creating approved vendor lists, and establishing guardrails that project teams couldn't step outside of.

The core principle: unless you own the scope, construction teams will do whatever they want. Influence isn't enough. Control matters.

Digital commissioning presents even steeper challenges. True 100% digital commissioning requires a clearly stated plan from the beginning, with every trade, manufacturer, constructor, and consultant understanding their role and expectations. The problem is that every project has a different commissioning plan—or no plan at all—and commissioning agents often just want to finish quickly.

Without proper commissioning, even well-specified infrastructure delivers inconsistent results and creates operational headaches that property teams blame on "the technology" rather than poor implementation.

Then there's vendor lock-in. When asked how to escape it, the response was frank: you probably can't. Vendor business models are built around recurring revenue. The best defense is being prescriptive in RFPs to create environments of openness, ensuring that when licensing models change or fees increase, you have viable exit options.

The goal isn't escaping all vendor relationships—it's avoiding getting so deep with any single vendor that you can't leave. That means insisting on open data standards, maintaining control of data, and structuring contracts that preserve leverage.

People and Process: The Human Side of Maturity

Here's the mistake that quietly kills programs: relying too heavily on experts without building broader capability across the organization.

Sutic described having someone on her team who became a crutch—"call so and so and he would fix things and everybody went along their merry way". When that person left, the organization hadn't built sufficient internal capacity. Property managers are always busy, and adding something new feels like too much. The discomfort comes from unfamiliarity. Education helps, but building confidence through hands-on experience matters more.

So how do you become a smart building champion in an organization with lots of leadership layers? Sutic's advice was straightforward: find who you need to take out for a beer. Most leaders aren't trying to be difficult—if they see you're interested in something, trying to accomplish something, and not being a jerk about it, they'll usually spend time with you.

Lambrinos emphasized creating a team of champions rather than centralizing expertise. When one group is the central focus and ownership isn't distributed throughout the organization, others always see it as "your thing"—something they call someone else about when it breaks. Building relationships at all levels ensures that when technology initiatives reach investment, asset management, or property teams, people already know what it is and who's behind it.

Sutic added another dimension: making it the building team's project rather than the innovation team's project. That means understanding why initiatives matter to tenants and owners—the real stakeholders—and building trust that you can accurately interpret their needs. The leadership stance becomes: "How can I help you shine, so that you're the one actually delivering and doing what needs to be done, and I'm happy to be in the background making that connection".

Programs succeed when knowledge lives with property teams rather than one smart building guru. When site staff move from dependence to confidence. When internal champions influence through relationships built on trust rather than formal authority.

Smart Infrastructure as the New Standard

For commercial real estate landlords, "smart" has graduated from innovation project to infrastructure category.

The trajectory these programs describe moves from securing foundational connectivity and cybersecurity, to treating technology like utilities—critical, continuous, and non-negotiable—to building organizational fluency around digital building operations. Smart systems are now expected in prime buildings, with automated energy adjustment, secure networks, and connected systems becoming part of what defines a top-tier asset.

This shift changes budget conversations. Spending moves from discretionary innovation funds to baseline capital planning. Property teams shift from tech-averse to tech-dependent. Tenant conversations shift from "look at our smart features" to "here's how the building performs."

What's on landlords' minds right now isn't whether to invest in building technology—it's how to do it well across diverse portfolios with finite resources. How to fight construction inertia without alienating the teams they need. How to build internal capability without depending on expensive experts. How to preserve flexibility with vendors while accepting that recurring fees are the price of doing business.

Technology maturity happens when organizations stop treating smart buildings as a separate initiative and start embedding digital infrastructure into how they define, design, operate, and market their assets.

For landlords managing office portfolios, that embedding process protects long-term value in a market where tenants increasingly expect buildings to just work—efficiently, securely, and intelligently—without thinking about the technology that makes it happen. Connected buildings become like elevators: you only notice them when they're missing or broken.

Keep Reading: Quadreal’s Quest for the Operations of the Future

Office landlords are stuck in a paradox. Tenants expect modern buildings that just work—connected, secure, efficient. Investors question why you're spending capital on technology infrastructure that wasn't in the original asset plan. And meanwhile, your buildings vary wildly—Class A downtown towers next to aging suburban assets, each with different ownership structures and joint ventures—making any standardized approach nearly impossible.

The question isn't whether to invest in smart building technology anymore. The question is: how do you actually do this across a real portfolio without burning credibility, blowing budgets, or creating a dependency on a single expert who becomes a crutch for the entire organization?

At NexusCon's Building Owner PreCon, three CRE leaders who've been running smart building programs for years gathered to talk about what's actually working. Thano Lambrinos, VP of Digital Buildings at QuadReal Property Group, Nada Sutic, Director of Sustainability, Innovation & National Programs at Epic Investment Services, and Grigor Hadjiev, Head of Real Estate Development Europe & Global Head of Innovation at PIMCO Prime Real Estate, all manage office properties as landlords—not owner-occupiers with direct control over operations.

They didn't talk about innovation or tenant experience apps. They talked about networks, cybersecurity, and construction fights. They talked about how to stop justifying every technology investment with a spreadsheet. And they made the case that the real maturity move is treating smart building infrastructure like elevators—expected, essential, and no longer requiring exhaustive ROI justification.

Their programs have been running for years—some as long as seven and a half—and they've moved past pilots into portfolio-wide implementation. What they've learned offers a clearer picture of what maturity looks like when you're protecting asset value across diverse portfolios.

The Landlord Reality Check: Back to Fundamentals

Here's what didn't work: chasing tenant experience apps and return-to-office features while ignoring the infrastructure underneath.

When Nada Sutic joined Epic Investment Services in 2022, the market was still excited about bells and whistles for bringing people back to the office. That enthusiasm evaporated fast. What remained was a harder question: how do you manage risk across a portfolio where buildings range from 800,000-square-foot downtown towers to 50,000-square-foot suburban B and C class assets?

The answer wasn't sexy. Base building networks. Cybersecurity protocols. Operational visibility. As Sutic put it: "I need to have a base building network and I need to have some cyber security in place".

Getting budgets approved hit a wall. Property managers didn't know how to sell these investments to the asset managers who approve budgets. Epic's solution was practical: go client by client, sit down with asset management teams, and stop talking about "smart buildings." Frame it as risk management, tenant experience, enhanced operations, and cost management. The message was realistic: "You don't have to do everything right now. We'd love it if you did, but understand that there are risks if you don't, and that's okay. We just need to be able to manage that and be aware".

Budgets started getting approved. Epic now has base building networks with cybersecurity protections across the portfolio. Progress came through education and reasonable conversations, not better technology.

Beyond ROI: When Smart Tech Becomes the New Elevator

Here's the counterintuitive move that unlocked these programs: they stopped trying to prove ROI on every technology investment.

This goes against everything the industry preaches. Everyone assumes you need better KPIs and more rigorous measurement. But spending months calculating business cases for smart building investments was, as one leader put it, just burning time on metrics that ultimately didn't matter.

The problem with ROI calculations is they treat technology like a discretionary expense rather than infrastructure. But real estate investment decisions don't actually work that way. They're based on conviction. You need to know who the decision maker is and what will convince them—a coffee conversation, a small demonstration, making their life easier—not a 47-page financial model.

Thano Lambrinos was blunt about this. When you present business cases, almost no one goes back to check whether every projected number was hit. But everyone intrinsically knows that integrating building systems, improving visibility into data, centralizing operations, and streamlining construction creates value. As Lambrinos put it: "It's kind of silly to think that there's no value in integrating a whole bunch of building systems and getting better visibility and data. There's no value in centralizing the way that we operate. There's no value in streamlining construction. That's just really dumb."

His advice? Don't be afraid to make things a little fuzzy. Investment committee presentations contain plenty of hopeful projections—technology programs should do the same to get moving. There are real returns to point to around energy savings, construction efficiency, and maintenance optimization. It just takes time.

Sutic drew a parallel to sustainability's journey. Fifteen years ago, the question was whether green buildings created value. The answer was "we're pretty sure". Eventually, solid studies using real lease data proved that certified green buildings commanded more rent. The value existed before it could be precisely measured.

Technology follows the same pattern. Can you build a 30-story building without elevators? Sure, but you don't. Elevators are expensive. Nobody demands an ROI calculation before installing them because they're infrastructure, not amenities.

That's the shift. Smart building systems are moving into that same category—expected components of how modern buildings function, not optional upgrades requiring exhaustive justification. When landlords make that mental shift, technology budgets move from discretionary innovation funds to baseline capital planning.

Smart as Standard: Table Stakes for Prime Office Space

Once technology becomes infrastructure, the marketing conversation changes. Don't market technology as a standalone feature. Lambrinos described River South, a QuadReal building in Austin, Texas—the first development south of the river in a market flooded with vacant office space. The building hit 100% occupancy not because of its technology alone, but because it combined beautiful design, good amenitization, an amazing sustainability program, and technology into a compelling whole.

Talk about outcomes rather than features. Don't market sensors—explain what those sensors accomplish. But the conversation is also evolving beyond marketing. Prime buildings now have automated energy adjustment based on temperature and occupancy. They have digital security protections. The more the industry matures, the more these capabilities are presented as integral to prime product rather than as something separate.

Lambrinos made the comparison explicit: "Show me the return on the artwork that you spend $200,000 on in the lobby. Show me the return on the marble that you put in the bathrooms". Nobody asks those questions because lobby finishes are understood as part of what makes a building competitive. Technology infrastructure is moving into the same category.

Maturity Moves: Building Programs that Stick

So how do you move from startup phase to portfolio-wide operation? It's not about technology choices—it's about organizational muscle.

Lambrinos outlined QuadReal's progression: first came simple connectivity and visibility into what systems existed and where. Next was integrating those connected systems. In parallel, they built their own tenant experience environment rather than paying premium prices for vendor solutions. Then they expanded scope to include not just technology but every building system except the concrete, glass, finishes, and roof.

The key to success was having control or influence over scope across the board, because trying to layer technology over systems you don't control is "kind of a lost cause".

One specific move unlocked broader deployment: convincing asset management to put a network into a single building. That success enabled rolling out a massive portfolio-wide program. Small wins open doors to bigger moves.

For PIMCO Prime Real Estate's building signature initiative, the path involved creating a blueprint covering multiple areas simultaneously: collecting environmental data through smart meters, implementing comfort and occupancy measurement, establishing a central data lake for decision making, and building cybersecurity protections. Over five years, they've connected over 1 million square meters of space.

Maturity comes through repeatable, scaled decisions—not one-off pilots. It requires executive alignment on clear outcomes early. It demands proving value through small wins. It prioritizes connectivity and integration before chasing analytics or AI applications.

Overcoming Industry Friction

Even well-funded programs with executive support crash into construction teams and vendor lock-in.

When asked about getting construction teams to buy in, the answer was simple: "fight". Construction teams don't want to change how they've operated for 30 years. The solution required creating standard specifications, embedding digital building teams in projects, taking over scope, creating approved vendor lists, and establishing guardrails that project teams couldn't step outside of.

The core principle: unless you own the scope, construction teams will do whatever they want. Influence isn't enough. Control matters.

Digital commissioning presents even steeper challenges. True 100% digital commissioning requires a clearly stated plan from the beginning, with every trade, manufacturer, constructor, and consultant understanding their role and expectations. The problem is that every project has a different commissioning plan—or no plan at all—and commissioning agents often just want to finish quickly.

Without proper commissioning, even well-specified infrastructure delivers inconsistent results and creates operational headaches that property teams blame on "the technology" rather than poor implementation.

Then there's vendor lock-in. When asked how to escape it, the response was frank: you probably can't. Vendor business models are built around recurring revenue. The best defense is being prescriptive in RFPs to create environments of openness, ensuring that when licensing models change or fees increase, you have viable exit options.

The goal isn't escaping all vendor relationships—it's avoiding getting so deep with any single vendor that you can't leave. That means insisting on open data standards, maintaining control of data, and structuring contracts that preserve leverage.

People and Process: The Human Side of Maturity

Here's the mistake that quietly kills programs: relying too heavily on experts without building broader capability across the organization.

Sutic described having someone on her team who became a crutch—"call so and so and he would fix things and everybody went along their merry way". When that person left, the organization hadn't built sufficient internal capacity. Property managers are always busy, and adding something new feels like too much. The discomfort comes from unfamiliarity. Education helps, but building confidence through hands-on experience matters more.

So how do you become a smart building champion in an organization with lots of leadership layers? Sutic's advice was straightforward: find who you need to take out for a beer. Most leaders aren't trying to be difficult—if they see you're interested in something, trying to accomplish something, and not being a jerk about it, they'll usually spend time with you.

Lambrinos emphasized creating a team of champions rather than centralizing expertise. When one group is the central focus and ownership isn't distributed throughout the organization, others always see it as "your thing"—something they call someone else about when it breaks. Building relationships at all levels ensures that when technology initiatives reach investment, asset management, or property teams, people already know what it is and who's behind it.

Sutic added another dimension: making it the building team's project rather than the innovation team's project. That means understanding why initiatives matter to tenants and owners—the real stakeholders—and building trust that you can accurately interpret their needs. The leadership stance becomes: "How can I help you shine, so that you're the one actually delivering and doing what needs to be done, and I'm happy to be in the background making that connection".

Programs succeed when knowledge lives with property teams rather than one smart building guru. When site staff move from dependence to confidence. When internal champions influence through relationships built on trust rather than formal authority.

Smart Infrastructure as the New Standard

For commercial real estate landlords, "smart" has graduated from innovation project to infrastructure category.

The trajectory these programs describe moves from securing foundational connectivity and cybersecurity, to treating technology like utilities—critical, continuous, and non-negotiable—to building organizational fluency around digital building operations. Smart systems are now expected in prime buildings, with automated energy adjustment, secure networks, and connected systems becoming part of what defines a top-tier asset.

This shift changes budget conversations. Spending moves from discretionary innovation funds to baseline capital planning. Property teams shift from tech-averse to tech-dependent. Tenant conversations shift from "look at our smart features" to "here's how the building performs."

What's on landlords' minds right now isn't whether to invest in building technology—it's how to do it well across diverse portfolios with finite resources. How to fight construction inertia without alienating the teams they need. How to build internal capability without depending on expensive experts. How to preserve flexibility with vendors while accepting that recurring fees are the price of doing business.

Technology maturity happens when organizations stop treating smart buildings as a separate initiative and start embedding digital infrastructure into how they define, design, operate, and market their assets.

For landlords managing office portfolios, that embedding process protects long-term value in a market where tenants increasingly expect buildings to just work—efficiently, securely, and intelligently—without thinking about the technology that makes it happen. Connected buildings become like elevators: you only notice them when they're missing or broken.

Keep Reading: Quadreal’s Quest for the Operations of the Future

This is a great piece!

I agree.