Making Decarb Pay: Turning Sustainability from Expense to Engine

Building owners face competing pressures around decarbonization. Some have mandates with real timelines. Others are watching those commitments quietly fade. Either way, when the payback horizon stretches beyond a decade and capital is tight, "doing the right thing" isn't enough to move the needle.

The problem isn't intent. It's that the people who actually manage buildings have little incentive to make it happen.

At a recent NexusCon session emceed by Danielle Radden of Facil.ai, leaders from healthcare, data centers, and higher education shared how they've turned this challenge on its head. Their lesson: decarbonization doesn't have to be a cost center. When structured right, it becomes self-funding, operationally valuable, and politically defensible. The organizations getting real results aren't just chasing technology—they're redesigning motivation loops so that sustainability makes business sense for everyone involved.

This isn't another article about sustainability aspirations. It's about the mechanics of making decarbonization pay: how to align operators, tenants, and finance teams so carbon reduction delivers measurable financial and operational rewards. And critically, how to structure programs so the savings stick.

The ROI Gap in Building Decarbonization

For most building owners, sustainability lives in a reporting silo. It shows up in annual reports and ESG disclosures, but it rarely connects to the day-to-day decisions that move money and change behavior.

As session emcee Danielle Radden framed it: "Decarb doesn't sell itself. What's in it for me?"

That question cuts to the core of why so many decarbonization initiatives stall. The motivation to act has to feel bigger than the comfort of doing nothing. For building owners, that means moving past carbon as an abstract goal and making it tangible: dollars saved, systems optimized, tenants satisfied, teams empowered.

The speakers at NexusCon showed exactly how they've done this across very different building types. What they have in common is striking: they all built programs where decarbonization creates value that people can see, touch, and benefit from directly.

Sustainability as a Cost Center—Until It Isn't

Todd Cohen, Director of Strategic Sourcing and Facilities Infrastructure at Adventist HealthCare, flipped the equation. Instead of treating sustainability as an expense line, he embedded it directly into compensation structures, vendor contracts, and performance reviews.

"We built decarbonization into contracts, sourcing, and incentives," Cohen explained. "Once bonuses were tied to results, engagement skyrocketed."

The case study speaks for itself. At White Oak Medical Center, Cohen's team used fault detection and diagnostics (FDD) to justify retro-commissioning multiple air-handling units. The facility had been experiencing unexplained shutoffs, pressure variances, and economizer sequences that weren't performing to design intent. Instead of treating these as isolated maintenance issues, they used the data to build a business case.

The results:

- $11.8M in annual utility expenses analyzed and verified

- $3.5M in energy conservation measures implemented

- $2.4M in rebates earned

- 6,450 MT CO₂e avoided annually

This wasn't just an energy project. It solved operational problems, reduced complaints, and gave the facilities team a tangible win they could point to. And because performance was tied to compensation across operations, engineering, and infrastructure teams, everyone had skin in the game.

Building Owner takeaway: Don't start with technology. Start with incentives. When every department shares in the reward, decarbonization becomes self-motivating.

Balancing Efficiency and Reliability in Mission-Critical Environments

In data centers, efficiency often loses to uptime. Downtime costs are measured in millions, and any optimization that threatens availability gets shut down fast.

Jenny Gerson, Vice President of Sustainability at DataBank, reframed the conversation. Instead of positioning efficiency as a tradeoff, she made it part of risk management.

"Our tenants pay for overhead power," Gerson said. "The more efficient we are, the more everyone wins."

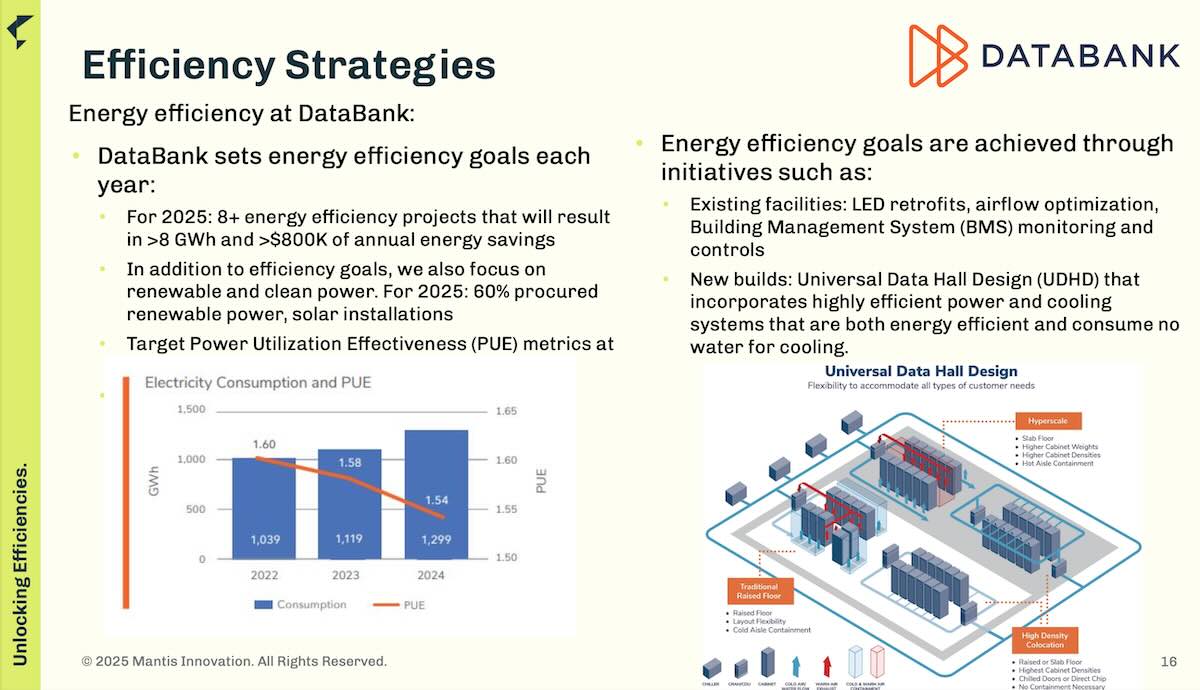

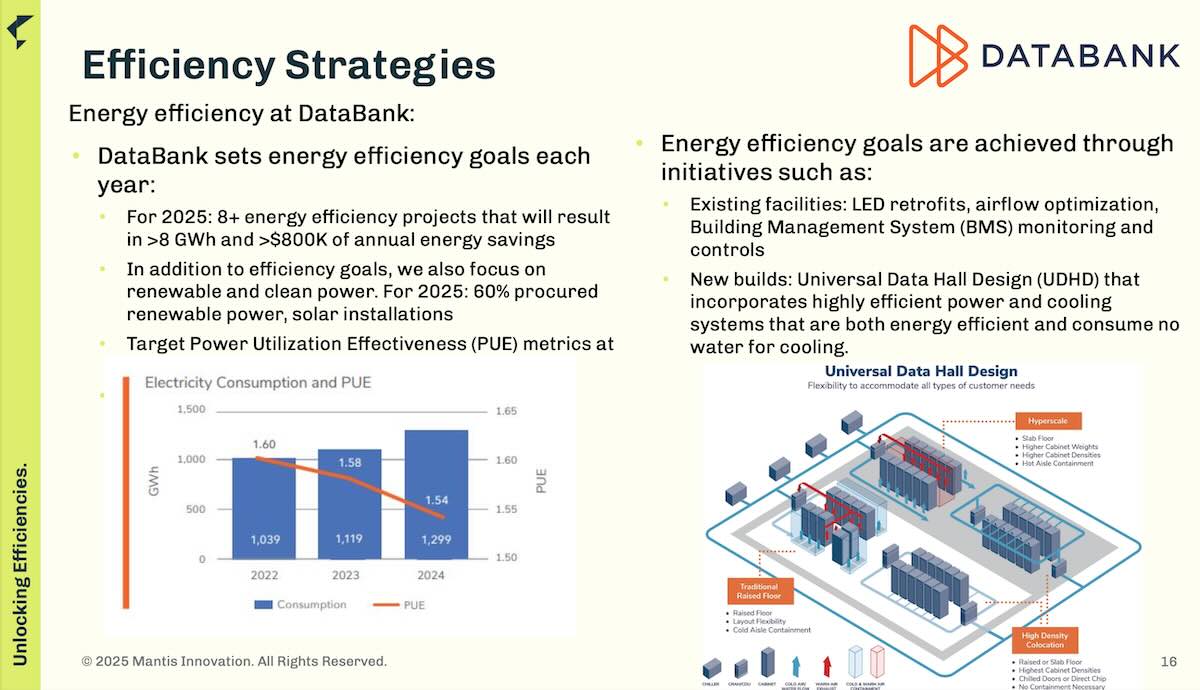

DataBank set aggressive efficiency goals for 2025: eight projects delivering more than 8 GWh and $800,000 in annual savings. But the key wasn't just setting goals—it was tying them to bonuses across multiple business units. Operations, infrastructure, and sustainability teams all had a financial stake in hitting the targets.

Working with Mike Bendewald from Mantis Innovation, Gerson's team tied performance metrics like Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) to annual bonuses. The result: measurable savings without compromising uptime.

Beyond the immediate projects, Gerson sees opportunity in advanced building management system (BMS) capabilities: AI-driven fault detection, dynamic load balancing, and real-time setpoint tuning. These tools can optimize cooling systems and predict maintenance needs while protecting uptime.

But there's tension. As Gerson noted, "BMS systems are really powerful. There's a lot of automation they can do. But tenants get nervous. They don't want everything automated. They don't want AI running the show."

That tension—between what's possible and what's acceptable—defines the challenge for mission-critical facilities. The answer isn't to automate everything. It's to sequence changes carefully, demonstrate results, and build trust before expanding automation.

Building Owner takeaway: Reliability and efficiency aren't competing goals. A well-sequenced BMS protects uptime and lowers operating costs. The key is proving it works on a small scale before expanding.

Moving from Projects to Programs

One-off projects deliver short-term wins. But real returns come from structured programs that compound over time.

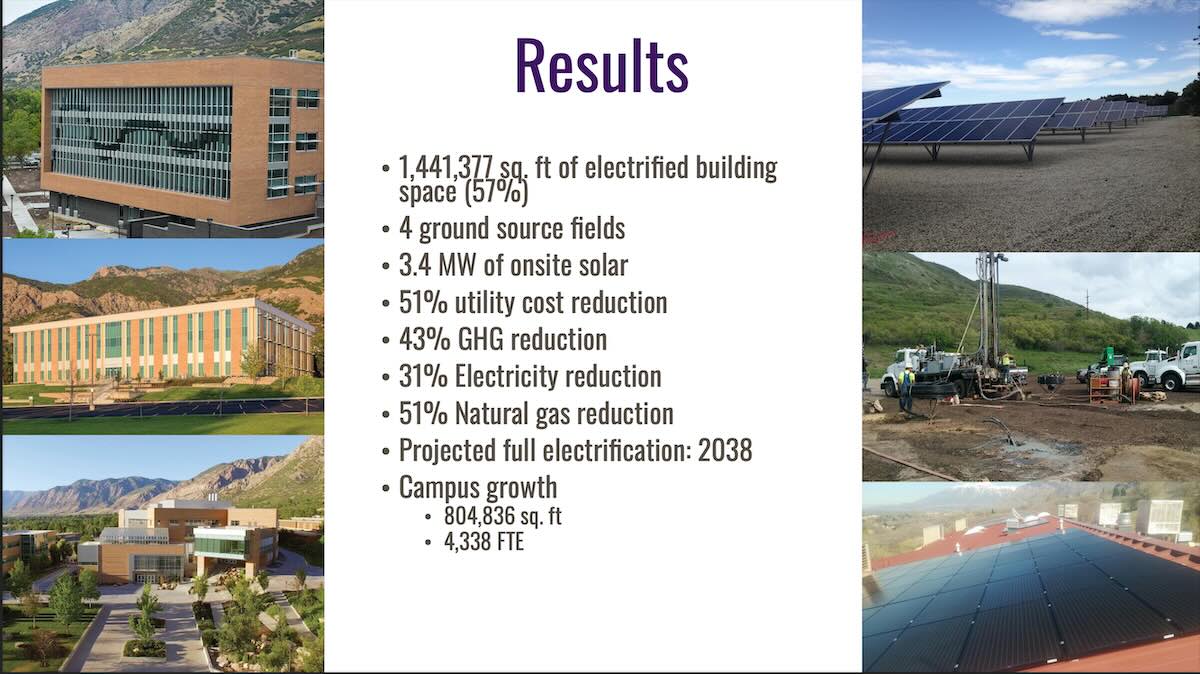

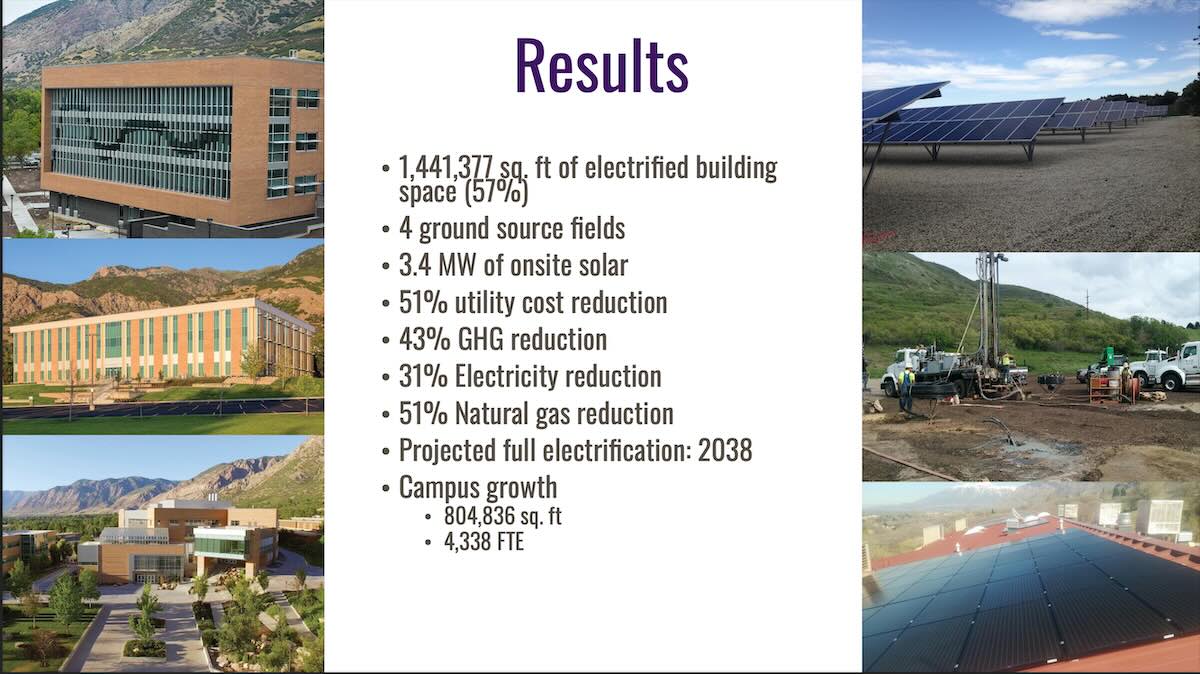

Justin Owen, Interim Director of Operations at Weber State University, built a $5 million revolving energy fund that reinvests verified savings into new projects. His VP's direction was simple but non-negotiable: "The savings must be documented, and the savings must be real."

Since launching the program, Weber State has:

- Electrified 57% of campus buildings

- Installed 3.4 MW of onsite solar

- Cut utility costs by 51% and GHG emissions by 43%

- Generated $30 million in cumulative savings

The funding model is elegant. Energy savings augment existing capital budgets, creating synergy between energy management and capital planning. Instead of fighting for a slice of the budget every year, the energy program funds itself and grows over time.

This approach requires discipline. Every project must be measured, every dollar accounted for, and every reinvestment decision justified. But that rigor is what makes the program defensible. When administrators ask whether the energy fund is working, Owen has thirty million reasons to say yes.

Building Owner takeaway: Treat your energy program like a flywheel. Document results, reinvest them, and protect them. Once the program proves itself, it becomes politically untouchable.

Technology Without Buy-In

The most sophisticated analytics fail without human cooperation.

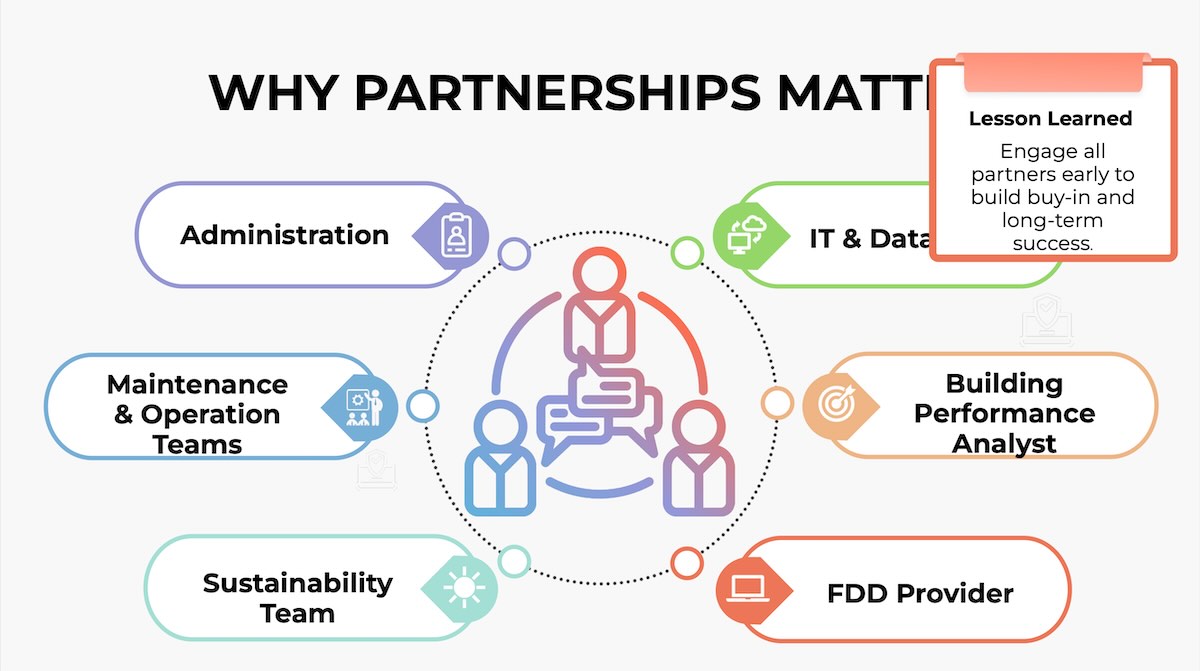

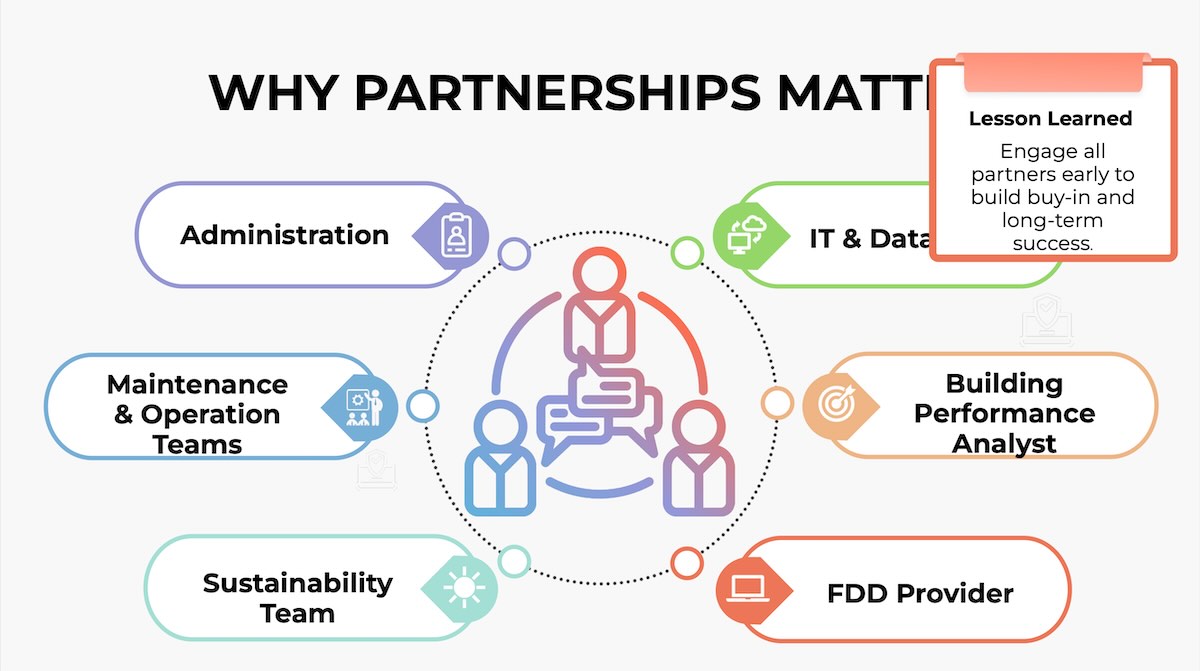

Amanda Alvarado from HEAPY, Nick Cassidy from BuildingLogix, and Asher Ensmenger from Indiana University showed how partnerships drive long-term success in monitoring-based commissioning.

"You can't just plug in analytics and expect buildings to fix themselves," Alvarado explained. "You need people, process, and technology working together."

Their monitoring-based commissioning program at Indiana University identified over 30 issues—malfunctioning sensors, leaking coils, control faults—worth $185,000 in potential savings. But the real breakthrough wasn't technical. It was cultural.

Monthly review meetings built trust between facilities, IT, and sustainability teams. Issues were logged in JIRA, assigned to specific people, tracked through resolution, and documented for future reference. The comment section became a collaboration tool instead of an email black hole.

Ensmenger, the energy engineer at IU, put it plainly: "My goal is to be invisible. If I'm doing my job right, building occupants don't know I exist."

That invisibility requires deep collaboration. The FDD system flags problems, but facilities staff solve them. The sustainability team tracks savings, but operations gets credit for execution. IT ensures data flows correctly, but everyone shares the win.

What made this work wasn't just good software. It was clear roles, regular communication, and a service agreement structured to reward collaboration instead of just software installation.

Building Owner takeaway: Technology flags problems; people solve them. Structure your service agreements to reward collaboration, not just software installation. Monthly reviews aren't overhead—they're the mechanism that makes the whole system work.

The Psychology of Motivation

Danielle Radden opened the session with a simple question: "What motivates you?"

Answers from the audience ranged from saving money to leaving a cleaner planet. All valid. But Radden pushed further.

"Motivation is about rewards," she said. "The reward has to feel bigger than the comfort of doing nothing."

The organizations making decarbonization pay have one thing in common: they redesigned motivation loops at every level.

Adventist HealthCare rewards performance. Bonuses are tied to measurable sustainability outcomes across operations, engineering, and infrastructure teams.

DataBank aligns tenant costs with efficiency. When PUE goes down, everyone benefits—the building owner saves on operating costs, and tenants pay less for overhead power.

Weber State reinvests savings to self-fund progress. Every dollar saved feeds back into the next round of projects, creating a compounding effect.

Indiana University empowers staff to own success. Energy engineers work with facilities teams as partners, not auditors, and everyone shares credit for wins.

Building Owner takeaway: Behavioral design matters as much as building design. When people don't feel the win personally, your program won't survive the next budget cycle. Make the rewards tangible, immediate, and distributed across multiple teams.

Making Decarbonization Pay: Common Findings

The presentations came from different sectors—healthcare, data centers, higher education—but the patterns were remarkably consistent.

First, incentives matter more than intent. Every successful program tied financial or career rewards directly to sustainability outcomes. When bonuses, performance reviews, or budget allocations depend on hitting targets, behavior changes fast.

Second, documentation is non-negotiable. All three organizations emphasized verified savings, not projected savings. Measurement and verification aren't just for grant applications. They're the foundation of political credibility and long-term funding.

Third, collaboration beats automation. The most sophisticated BMS or FDD system won't fix anything if facilities staff don't trust it. Success requires partnerships across teams—operations, IT, sustainability, finance—with clear roles and regular communication.

Fourth, programs beat projects. One-off initiatives deliver wins, but structured programs that reinvest savings compound over time. The organizations generating the most value treat energy management as a long-term funding mechanism, not a one-time fix.

Fifth, efficiency serves operations. The best decarbonization projects don't just cut carbon—they solve operational problems. Fixed air handlers, better temperature control, reduced complaints, improved uptime. When energy projects make buildings work better, they become operationally defensible, not just environmentally virtuous.

Conclusion: Decarbonization as a Business Model

The organizations that win at decarbonization don't just manage emissions—they manage incentives.

The formula is simple but powerful:

- Tie rewards to measurable outcomes

- Use data to verify impact, not justify investment

- Reinvest savings to keep the cycle alive

As Danielle Radden closed the session: "If you don't have a plan for what to do with your savings, that's your first project."

Decarbonization isn't a feel-good initiative. It's a business model shift. When you make it pay, everyone stays motivated to keep improving. The pressure to decarbonize isn't going away, but it doesn't have to be a burden. Done right, it becomes self-funding, operationally valuable, and politically untouchable.

That's when sustainability stops being an expense and starts being an engine.

Building owners face competing pressures around decarbonization. Some have mandates with real timelines. Others are watching those commitments quietly fade. Either way, when the payback horizon stretches beyond a decade and capital is tight, "doing the right thing" isn't enough to move the needle.

The problem isn't intent. It's that the people who actually manage buildings have little incentive to make it happen.

At a recent NexusCon session emceed by Danielle Radden of Facil.ai, leaders from healthcare, data centers, and higher education shared how they've turned this challenge on its head. Their lesson: decarbonization doesn't have to be a cost center. When structured right, it becomes self-funding, operationally valuable, and politically defensible. The organizations getting real results aren't just chasing technology—they're redesigning motivation loops so that sustainability makes business sense for everyone involved.

This isn't another article about sustainability aspirations. It's about the mechanics of making decarbonization pay: how to align operators, tenants, and finance teams so carbon reduction delivers measurable financial and operational rewards. And critically, how to structure programs so the savings stick.

The ROI Gap in Building Decarbonization

For most building owners, sustainability lives in a reporting silo. It shows up in annual reports and ESG disclosures, but it rarely connects to the day-to-day decisions that move money and change behavior.

As session emcee Danielle Radden framed it: "Decarb doesn't sell itself. What's in it for me?"

That question cuts to the core of why so many decarbonization initiatives stall. The motivation to act has to feel bigger than the comfort of doing nothing. For building owners, that means moving past carbon as an abstract goal and making it tangible: dollars saved, systems optimized, tenants satisfied, teams empowered.

The speakers at NexusCon showed exactly how they've done this across very different building types. What they have in common is striking: they all built programs where decarbonization creates value that people can see, touch, and benefit from directly.

Sustainability as a Cost Center—Until It Isn't

Todd Cohen, Director of Strategic Sourcing and Facilities Infrastructure at Adventist HealthCare, flipped the equation. Instead of treating sustainability as an expense line, he embedded it directly into compensation structures, vendor contracts, and performance reviews.

"We built decarbonization into contracts, sourcing, and incentives," Cohen explained. "Once bonuses were tied to results, engagement skyrocketed."

The case study speaks for itself. At White Oak Medical Center, Cohen's team used fault detection and diagnostics (FDD) to justify retro-commissioning multiple air-handling units. The facility had been experiencing unexplained shutoffs, pressure variances, and economizer sequences that weren't performing to design intent. Instead of treating these as isolated maintenance issues, they used the data to build a business case.

The results:

- $11.8M in annual utility expenses analyzed and verified

- $3.5M in energy conservation measures implemented

- $2.4M in rebates earned

- 6,450 MT CO₂e avoided annually

This wasn't just an energy project. It solved operational problems, reduced complaints, and gave the facilities team a tangible win they could point to. And because performance was tied to compensation across operations, engineering, and infrastructure teams, everyone had skin in the game.

Building Owner takeaway: Don't start with technology. Start with incentives. When every department shares in the reward, decarbonization becomes self-motivating.

Balancing Efficiency and Reliability in Mission-Critical Environments

In data centers, efficiency often loses to uptime. Downtime costs are measured in millions, and any optimization that threatens availability gets shut down fast.

Jenny Gerson, Vice President of Sustainability at DataBank, reframed the conversation. Instead of positioning efficiency as a tradeoff, she made it part of risk management.

"Our tenants pay for overhead power," Gerson said. "The more efficient we are, the more everyone wins."

DataBank set aggressive efficiency goals for 2025: eight projects delivering more than 8 GWh and $800,000 in annual savings. But the key wasn't just setting goals—it was tying them to bonuses across multiple business units. Operations, infrastructure, and sustainability teams all had a financial stake in hitting the targets.

Working with Mike Bendewald from Mantis Innovation, Gerson's team tied performance metrics like Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) to annual bonuses. The result: measurable savings without compromising uptime.

Beyond the immediate projects, Gerson sees opportunity in advanced building management system (BMS) capabilities: AI-driven fault detection, dynamic load balancing, and real-time setpoint tuning. These tools can optimize cooling systems and predict maintenance needs while protecting uptime.

But there's tension. As Gerson noted, "BMS systems are really powerful. There's a lot of automation they can do. But tenants get nervous. They don't want everything automated. They don't want AI running the show."

That tension—between what's possible and what's acceptable—defines the challenge for mission-critical facilities. The answer isn't to automate everything. It's to sequence changes carefully, demonstrate results, and build trust before expanding automation.

Building Owner takeaway: Reliability and efficiency aren't competing goals. A well-sequenced BMS protects uptime and lowers operating costs. The key is proving it works on a small scale before expanding.

Moving from Projects to Programs

One-off projects deliver short-term wins. But real returns come from structured programs that compound over time.

Justin Owen, Interim Director of Operations at Weber State University, built a $5 million revolving energy fund that reinvests verified savings into new projects. His VP's direction was simple but non-negotiable: "The savings must be documented, and the savings must be real."

Since launching the program, Weber State has:

- Electrified 57% of campus buildings

- Installed 3.4 MW of onsite solar

- Cut utility costs by 51% and GHG emissions by 43%

- Generated $30 million in cumulative savings

The funding model is elegant. Energy savings augment existing capital budgets, creating synergy between energy management and capital planning. Instead of fighting for a slice of the budget every year, the energy program funds itself and grows over time.

This approach requires discipline. Every project must be measured, every dollar accounted for, and every reinvestment decision justified. But that rigor is what makes the program defensible. When administrators ask whether the energy fund is working, Owen has thirty million reasons to say yes.

Building Owner takeaway: Treat your energy program like a flywheel. Document results, reinvest them, and protect them. Once the program proves itself, it becomes politically untouchable.

Technology Without Buy-In

The most sophisticated analytics fail without human cooperation.

Amanda Alvarado from HEAPY, Nick Cassidy from BuildingLogix, and Asher Ensmenger from Indiana University showed how partnerships drive long-term success in monitoring-based commissioning.

"You can't just plug in analytics and expect buildings to fix themselves," Alvarado explained. "You need people, process, and technology working together."

Their monitoring-based commissioning program at Indiana University identified over 30 issues—malfunctioning sensors, leaking coils, control faults—worth $185,000 in potential savings. But the real breakthrough wasn't technical. It was cultural.

Monthly review meetings built trust between facilities, IT, and sustainability teams. Issues were logged in JIRA, assigned to specific people, tracked through resolution, and documented for future reference. The comment section became a collaboration tool instead of an email black hole.

Ensmenger, the energy engineer at IU, put it plainly: "My goal is to be invisible. If I'm doing my job right, building occupants don't know I exist."

That invisibility requires deep collaboration. The FDD system flags problems, but facilities staff solve them. The sustainability team tracks savings, but operations gets credit for execution. IT ensures data flows correctly, but everyone shares the win.

What made this work wasn't just good software. It was clear roles, regular communication, and a service agreement structured to reward collaboration instead of just software installation.

Building Owner takeaway: Technology flags problems; people solve them. Structure your service agreements to reward collaboration, not just software installation. Monthly reviews aren't overhead—they're the mechanism that makes the whole system work.

The Psychology of Motivation

Danielle Radden opened the session with a simple question: "What motivates you?"

Answers from the audience ranged from saving money to leaving a cleaner planet. All valid. But Radden pushed further.

"Motivation is about rewards," she said. "The reward has to feel bigger than the comfort of doing nothing."

The organizations making decarbonization pay have one thing in common: they redesigned motivation loops at every level.

Adventist HealthCare rewards performance. Bonuses are tied to measurable sustainability outcomes across operations, engineering, and infrastructure teams.

DataBank aligns tenant costs with efficiency. When PUE goes down, everyone benefits—the building owner saves on operating costs, and tenants pay less for overhead power.

Weber State reinvests savings to self-fund progress. Every dollar saved feeds back into the next round of projects, creating a compounding effect.

Indiana University empowers staff to own success. Energy engineers work with facilities teams as partners, not auditors, and everyone shares credit for wins.

Building Owner takeaway: Behavioral design matters as much as building design. When people don't feel the win personally, your program won't survive the next budget cycle. Make the rewards tangible, immediate, and distributed across multiple teams.

Making Decarbonization Pay: Common Findings

The presentations came from different sectors—healthcare, data centers, higher education—but the patterns were remarkably consistent.

First, incentives matter more than intent. Every successful program tied financial or career rewards directly to sustainability outcomes. When bonuses, performance reviews, or budget allocations depend on hitting targets, behavior changes fast.

Second, documentation is non-negotiable. All three organizations emphasized verified savings, not projected savings. Measurement and verification aren't just for grant applications. They're the foundation of political credibility and long-term funding.

Third, collaboration beats automation. The most sophisticated BMS or FDD system won't fix anything if facilities staff don't trust it. Success requires partnerships across teams—operations, IT, sustainability, finance—with clear roles and regular communication.

Fourth, programs beat projects. One-off initiatives deliver wins, but structured programs that reinvest savings compound over time. The organizations generating the most value treat energy management as a long-term funding mechanism, not a one-time fix.

Fifth, efficiency serves operations. The best decarbonization projects don't just cut carbon—they solve operational problems. Fixed air handlers, better temperature control, reduced complaints, improved uptime. When energy projects make buildings work better, they become operationally defensible, not just environmentally virtuous.

Conclusion: Decarbonization as a Business Model

The organizations that win at decarbonization don't just manage emissions—they manage incentives.

The formula is simple but powerful:

- Tie rewards to measurable outcomes

- Use data to verify impact, not justify investment

- Reinvest savings to keep the cycle alive

As Danielle Radden closed the session: "If you don't have a plan for what to do with your savings, that's your first project."

Decarbonization isn't a feel-good initiative. It's a business model shift. When you make it pay, everyone stays motivated to keep improving. The pressure to decarbonize isn't going away, but it doesn't have to be a burden. Done right, it becomes self-funding, operationally valuable, and politically untouchable.

That's when sustainability stops being an expense and starts being an engine.

This is a great piece!

I agree.