OT Device Management: The Infrastructure Problem Building Owners Can't Ignore

The Tsunami Building Beneath Your Feet

In an industry notorious for moving at glacial speed, when someone uses the word "tsunami," you pay attention.

Matt White, whose consulting firm IntelliBuild supports the smart buildings program at a major financial institution, doesn't deploy hyperbole lightly. Yet that's exactly how he describes what's coming down the pipeline for building owners who haven't gotten serious about device management.

"This is like a tsunami that's about to hit the industry," White explains. He's not talking about some distant threat—he's describing what's happening right now in glass towers across Manhattan and will spread to every commercial building in the not-too-distant future.

The dirty job nobody talks about in real estate: Knowing what devices you actually have, where they are, what risks they pose, and whether they work. It sounds mundane. It's not.

It's the difference between a building owner spending millions on emergency remediation versus spreading costs across multiple budget cycles. It's the difference between your building systems enabling operational efficiency versus becoming the source of compliance violations and security incidents.

For most building owners, this wave is coming whether they're ready or not.

Inside the Financial Services Wake-Up Call

To understand the scale of what's headed toward the industry, look at what major financial institutions are doing right now. These aren't organizations known for panic spending—they're methodical, risk-averse, and extremely good at calculating return on investment.

They're spending hundreds of millions of dollars on device management.

What triggered this massive spending? Specific regulatory requirements from agencies like the New York Department of Financial Services (NYDFS). By November 1, 2025, NYDFS will require organizations to "develop and maintain a comprehensive asset inventory of their information systems that includes key information tracking (e.g, owner, location, etc), policies for updating the asset inventory, and the procedure for disposing of information."

Joe Gaspardone, COO of Montgomery Technologies, puts this in broader context: "For the first time you've got compliance—we all knew this was going to come, but this is the first wave. NIST has released OT compliance standards."

The significance isn't just the new requirements—it's that compliance has never extended to building systems before. As Gaspardone explains, "When you're a publicly traded company or just a large private REIT, you are always doing compliance, and nothing has ever dipped down into the building. It's always been compliance at the organizational level, at the corporate level."

The liability is clear: "If you don't have control, and you don't have device management, you don't understand what you have, and ensuring that it's locked down, there's liability there."

This extends traditional IT asset management beyond corporate systems to operational technology in buildings. "Now they're coming back and saying you actually need to do this on all communicating devices that you have, including the building side. That's a massive change," White explains.

Here's what a comprehensive device remediation program looks like when regulators give you 90 days to fix compliance issues:

Full inventory of every networked device. Not just the big equipment—every controller, switch, and access point. Teams are literally crawling through telecom closets with clipboards and barcode scanners.

Classification of each device's cybersecurity posture. What firmware version is running? When was it last patched? What vulnerabilities are exposed? As White notes, "When they do a full IT asset management inventory, they want to know everything about the device; whether or not it's end-of-life or not, or if it's ever been upgraded, patched, maintained; everything related to it."

Programmatic approach to ongoing lifecycle management. This isn't a one-time audit. It's building the infrastructure to track and maintain thousands of devices across global portfolios.

The spending is massive precisely because they waited. These institutions are discovering devices that have been unmanaged for years, with legacy junk partially protected when barriers are built around the mess as a stop gap. The cost to remediate years of unmanaged devices and bring them into compliance is staggering.

But here's the thing—they have to do it, and fast. The alternative is facing regulatory penalties that could make the remediation costs look modest.

Why This Matters Beyond Financial Services

The regulatory pressure hitting banks is just the leading edge. White predicts the federal government will "continue to try to push this from beyond financial services to this should be a best practice that everyone is doing." The reasoning is stark: building infrastructure is "seen as one of the largest national security threats from a cyber perspective" because so much of it is legacy, lacks secure design and implementation by vendors who often do not have proper training or understanding of cyber best practices.

But compliance is only one driver. There are other forces making device management unavoidable:

Cybersecurity threats are escalating. Recent data shows building automation protocols are increasingly targeted in OT attacks, with building automation rising from 1% to 9% of all operational technology attacks in just one year. According to TXOne Networks, when a building automation engineering firm in Germany lost "control of many field devices (such as light switches, motion detectors, shutter controllers)" it led to a cyberattack in 2021, it wasn't an isolated incident—it was a preview of what's coming.

Smart building use cases depend on device reliability. Every sensor that goes offline breaks something else. Building owners are discovering this across multiple applications. As James Hare, a building systems specialist with ARUP, notes when discussing fault detection and diagnostics (FDD), "if you don't control the settings on those devices, you can then roll back all of your good work on your FDD optimizations."

But the dependencies extend far beyond energy analytics. There are two distinct challenges: devices that pass data to enable smart building use cases, and devices that simply need to be maintained to fulfill their basic function.

Rick Szcodronski, Chief Product Officer at Willow, describes the first category—devices that feed data to other systems. One client discovered they had "eight different IoT solutions" across their campus that needed management as "truly managed assets," from occupancy sensors that feed space utilization analytics to remote IoT sensor monitoring.

The second category includes devices that require ongoing maintenance and connectivity just to work as intended. Workplace equipment like connected fitness machines, AV systems in conference rooms, and smart appliances all depend on reliable network access to deliver their core functionality. As White explains, the goal is often ensuring building teams are "the ones finding out that there's an issue before the occupant does."

In both cases, device management failures have immediate operational impact—either breaking the data flows that power smart building insights or preventing basic building amenities from functioning properly.

The pattern is consistent: smart building applications fail when the underlying devices aren't properly discovered, classified, and maintained.

Insurance companies are taking notice. White reports seeing "insurance companies now looking at this program and saying, 'Wow, these are awesome programs that you guys are building. We would like to take these programs and recommend them out to our portfolio of owners, because this minimizes so much risk.'"

Competitive pressure is building. White predicts a future where device management becomes a differentiator between properties. For new developments, he sees an opportunity: "If I was a developer doing new properties, I would get this in place right away and say, I'm giving you an infrastructure that you will not have to worry about in five years."

The competitive dynamic may emerge as corporate tenants become more aware of how infrastructure affects their own technology initiatives. Companies facing massive remediation costs in their current buildings could eventually prioritize locations where device management is already solved, rather than inheriting someone else's technical debt.

The tsunami isn't just regulatory—it's economic, competitive, and operational.

What Device Management Actually Means

Most building owners think they're already doing device management. They're not. As Hare observes, "The vast majority of clients outside of certain industries are not really aware of this stuff. They have their BMS systems running. They have a contractor maintaining them." Gaspardone describes the common mindset: "Everybody thinks somebody else is responsible for this solution... about at least about half the time, maybe probably more, they think that they have it."

What they're actually doing is reactive maintenance—hoping their BMS contractor shows up when something breaks while assuming their IT vendor handles network security.

Real device management is a program, not a project. It has six components:

1. Discovery: What Devices Exist?

This is the literal dirty job. Gaspardone describes sending teams into telecom closets to "unravel a plate of spaghetti into clean lines that are intelligible." The process involves documenting every piece of equipment, its network infrastructure, understanding its purpose, and mapping connections that often lack proper labeling.

Hare explains Arup's approach, which combines physical inspections with network-based scanning for devices. But regardless of method, teams face the same underlying problem: "Documentation is not present. No one knows where the drawings live. No one has the right vendor contact... It's the wild wild west."

2. Assessment: What's Their Cybersecurity Posture?

Discovery reveals what devices exist, but assessment determines their security status. This means identifying firmware versions, patch histories, and whether devices appear on lists of known vulnerabilities. Some building owners work with technology partners to enrich this process—Willow, for example, integrates with Mapped, an independent data layer provider, to enhance device discoveries during network scans by identifying firmware versions and exposed devices.

Building owners often discover their systems have been neglected for years—firewalls that haven't been updated in a decade, BAS systems wide open to the internet.

3. Classification: How Do Devices Relate to Operations?

Moving beyond basic inventories requires understanding how devices connect to actual building operations. The challenge is visualizing relationships that aren't obvious from device lists alone. As Szcodronski explains, "Something as simple as a piece of HVAC equipment... has on average, in our Knowledge Graph, eight to 12 relationships."

That single piece of equipment isn’t just a line item—it’s tied to the room it sits in, the upstream and downstream equipment it depends on, the controller that operates it, the network that controller sits on, and the spaces it heats, cools, or ventilates. Each relationship creates dependencies that must be tracked if owners want a truly accurate picture of their building operations.

Some building owners are moving beyond Excel spreadsheets toward data layers—digital systems that can map these complex relationships between devices, equipment, and spaces. Whether built in-house or purchased from vendors like Willow, these platforms replace static spreadsheets with living, connected views of how assets relate. The approach varies—some use knowledge graphs, others rely on structured databases—but the common goal is the same: moving beyond a simple list of devices toward a system that shows how those devices actually work together in the building.

Data layer platforms add value across multiple phases of device management. They support discovery and assessment by unifying the raw device list (the asset register) with a knowledge graph that shows how each piece of equipment connects to controllers, networks, and spaces. They also help with classification by standardizing how devices are named and organized, avoiding the confusion of inconsistent labels across portfolios.

But their value extends far beyond device management—by combining asset registers and knowledge graphs with real-time data streaming from the building, they enable operational use cases ranging from energy optimization to predictive maintenance. As Szcodronski explains, 'Teams used to spend hours—sometimes a whole day—digging through old drawings or thumb drives to figure out how equipment was connected. With the knowledge graph, you get that answer in seconds.'"

4. Remediation: How Do You Fix the Problems?

Building owners take different approaches to fixing what they find. Some work with consultants to write specifications and manage multiple contractors through a bidding process. For example, ARUP often helps owners by scoping the work in detail, so local contractors can bid and execute under the owner’s oversight. This model gives owners flexibility and control, but also requires them to coordinate multiple vendors and ensure accountability.

Others prefer end-to-end service providers who handle both design and execution of converged networks. Montgomery Technologies, for instance, takes a turnkey approach—writing the specification, executing the work, and managing the network lifecycle as a managed service. For owners without the internal resources to manage multiple contractors, this one-stop-shop model reduces complexity and transfers more responsibility to the provider.

The remediation approach often depends on the building owner's internal capabilities, budget, and timeline. But the goal is consistent: creating managed, segmented networks where access is controlled and systems are properly integrated.

5. Maintenance: How Do You Keep Records Current?

This is where most programs fail. The challenge isn't just cleaning up the existing mess—it's preventing a return to chaos. Some building owners implement automated platforms for firmware management at scale, while others rely on structured manual processes with regular audit cycles.

As Gaspardone points out, buildings are constantly changing, and unmanaged networks deteriorate quickly: “You walk in eight years later, and there’s the firewall, and it’s exactly in the state it was when it was installed. There’s no subscription, there’s no updating, there’s nothing.”

The key insight from successful programs is establishing ongoing processes to prevent falling back into disorder, whether through technology solutions, service contracts, or internal procedures.

6. Setting Standards for Future Devices

The final piece—often overlooked—is establishing requirements for what devices can be installed going forward. As White notes, just selecting "open devices isn't enough anymore”. Smart device selection spends capital efficiently by considering the full lifecycle and avoids creating problems that require additional resources down the road.

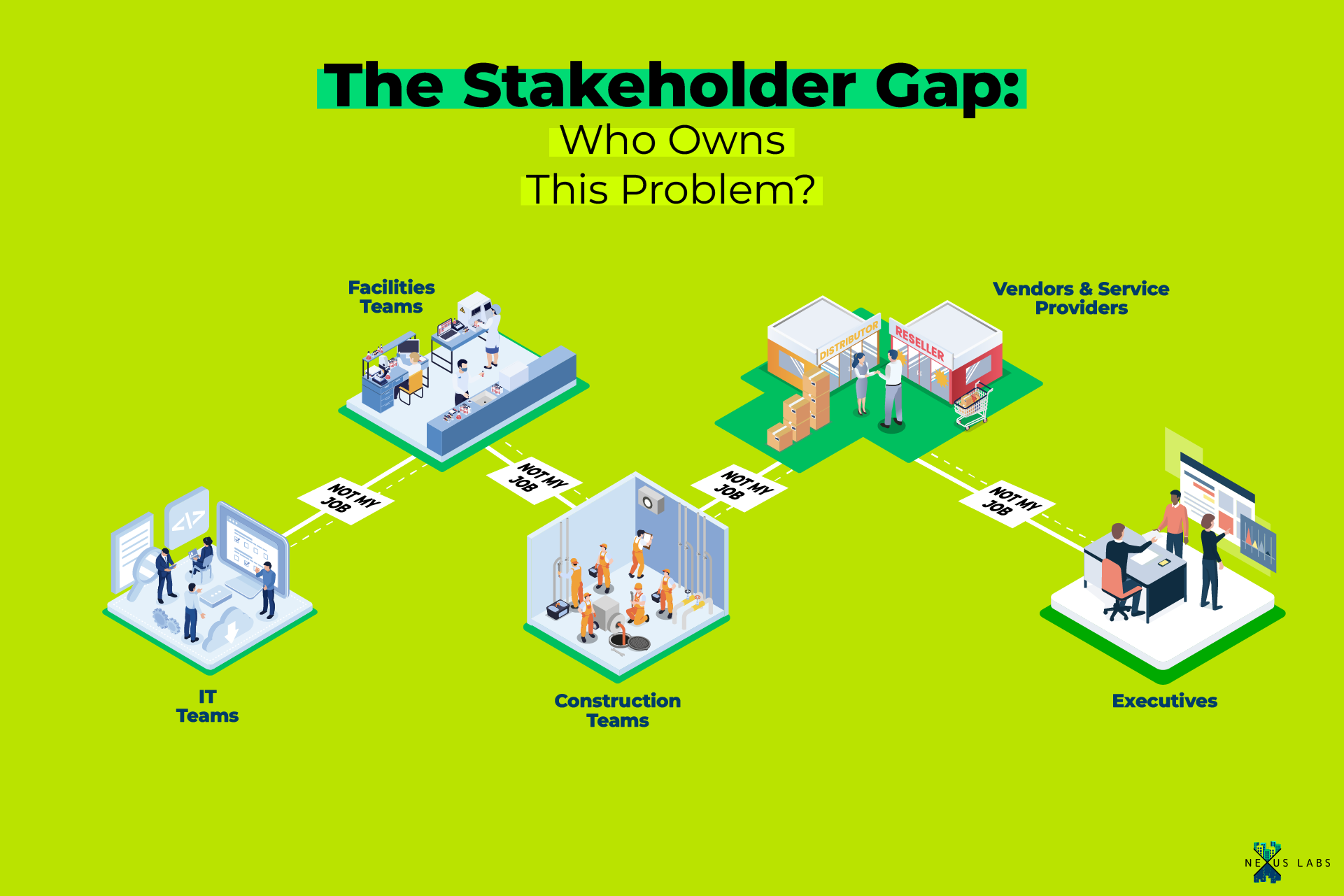

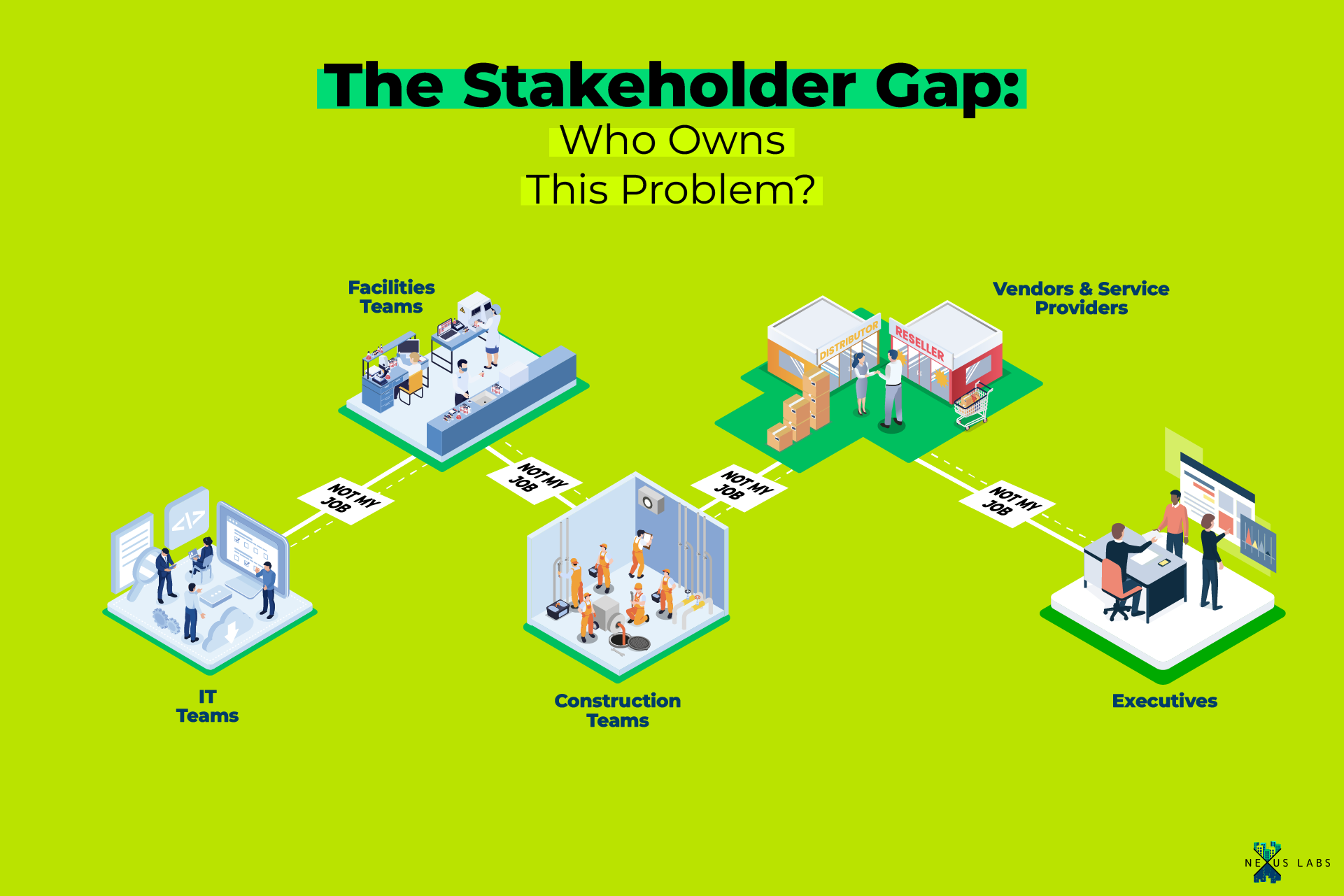

The Stakeholder Gap: Who Owns This Problem?

Here's why device management problems persist: nobody owns them. In most organizations, device management falls into a gap between multiple stakeholders who all assume someone else is handling it.

IT Teams see operational technology as outside their scope, focusing instead on corporate systems. In higher education and healthcare, where IT teams do engage with building systems, they often treat OT equipment like traditional IT assets, creating bureaucratic barriers that can slow building projects.

Facilities Teams are often focused on the immediate needs of building operations—keeping occupants comfortable, responding to hot and cold calls, and ensuring systems stay online. In that environment, it’s easy for long-term considerations like firmware updates or cybersecurity to take a back seat. As Matt White explains, facility managers make day-to-day equipment decisions that solve urgent problems, but those choices can have ripple effects for years to come, depending on the devices they select and the contractors they engage.

Construction Teams install devices during the build phase, then move on to the next project without any ongoing lifecycle responsibility. Everything gets delegated to low-bid contractors with no standards for network infrastructure and often leave little in the way of operational documentation or standards for device management.

Vendors and Service Providers are incentivized to avoid this responsibility entirely. The business model doesn't support it. As White explains, major facility management companies "refuse to put the contractual language on their side of anything related to cyber security, or networks. They will not do it. Their lawyers will not let them" except for special negotiations with top-tier clients. The liability exposure is too high and the expertise requirements too specialized for companies built around traditional building maintenance and service contracts.

Executives assume someone in the organization has device management covered. As Gaspardone explains, "Everybody thinks somebody else is responsible for this solution." Property managers assume corporate IT handles it, while IT assumes facilities management does.

The result: nobody raises their hand until compliance requirements or a security incident forces action. By then, the remediation costs are massive because the problem has been growing unmanaged for years. And if a security incident occurs first, the financial damage extends far beyond remediation. The hard costs of a data breach in the financial sector is in the millions. That's before accounting for operational downtime, regulatory fines, customer losses, and reputational damage that can take years to recover.

The Path Forward: Lessons for Building Owners

Assign ownership. Organizations need to decide which department will take responsibility for this challenge. Some, like Google, have expanded their network management teams to include OT devices alongside corporate IT. Others hire managed service providers or consultants to fill the gap.

Start budgeting now. As White warns, the timeline for addressing device management is longer than most building owners realize. By the time you understand what you have and develop a remediation plan, spreading those costs across multiple (read: 5 or more) budget cycles becomes essential. Waiting makes the problem exponentially more expensive.

Right-size your approach. The solution depends on your portfolio size and capabilities. Smaller building owners can implement structured manual inventories every six to twelve months, combined with clear standards for future device installations. Larger portfolios benefit from automated discovery tools and managed service providers who can execute consistently across multiple buildings.

Start with visibility. Understanding what devices you have is the foundational step, even if that information initially lives in a simple database that won't become immediately obsolete.

Don't wait for compliance to force action. Organizations moving proactively can spread costs across multiple budget cycles and avoid the emergency spending that financial institutions are experiencing now.

Use vendor partners where internal capacity doesn't exist. As Hare notes, unless you have a global company with this capability in-house, "it makes more sense to contract it out to service providers to help you get to that place."

Some building owners are turning to managed service providers to bridge the staffing gap entirely. Gaspardone's company, Montgomery Technologies, offers a service called Intelligent Riser for commercial office and multifamily owners, where they supplement the owner's lack of OT staff and perform device management on their behalf for a monthly fee. This approach recognizes that many building owners simply don't have—and may never have—the internal expertise to manage this problem themselves.

Recognize this is an ongoing program, not a one-time project. The goal isn't just cleaning up the existing mess—it's building systems and processes to prevent falling back into chaos.

The Competitive Reality

White's prediction cuts to the heart of why this matters: "A typical building owner may not yet have to be as aggressive as regulated institutions, but they should be afraid of the tsunami that's coming and start addressing it now."

Device management is no longer a nice-to-have. The mix of regulatory pressure, cybersecurity concerns, and operational dependencies means it’s becoming an expectation. Financial institutions are spending heavily because they waited, but not every owner will experience the same emergency timeline.

For most, the smart move is to assess your own level of risk and start planning accordingly. Acting now gives organizations the chance to spread costs across budget cycles, assign ownership, and build sustainable processes. Waiting often leads to compressed timelines and higher costs—but the scale and urgency depend on your portfolio, your systems, and your regulatory exposure.

Importantly, this isn’t just about compliance or risk avoidance. Building owners who put programs in place are better positioned to deliver on the smart building promises that many talk about but few achieve—fault detection that actually works, energy optimization that sticks, and systems that operate as intended.

Every month of delay shortens your runway, but starting now means you can move at a pace that matches your own risk profile and organizational priorities.

---

Keep Reading Links:

Marketplace helps you find network managers and consultants, data layer providers, and more

NexusCon '24 session on this topic.

Summary article on above session.

The Tsunami Building Beneath Your Feet

In an industry notorious for moving at glacial speed, when someone uses the word "tsunami," you pay attention.

Matt White, whose consulting firm IntelliBuild supports the smart buildings program at a major financial institution, doesn't deploy hyperbole lightly. Yet that's exactly how he describes what's coming down the pipeline for building owners who haven't gotten serious about device management.

"This is like a tsunami that's about to hit the industry," White explains. He's not talking about some distant threat—he's describing what's happening right now in glass towers across Manhattan and will spread to every commercial building in the not-too-distant future.

The dirty job nobody talks about in real estate: Knowing what devices you actually have, where they are, what risks they pose, and whether they work. It sounds mundane. It's not.

It's the difference between a building owner spending millions on emergency remediation versus spreading costs across multiple budget cycles. It's the difference between your building systems enabling operational efficiency versus becoming the source of compliance violations and security incidents.

For most building owners, this wave is coming whether they're ready or not.

Inside the Financial Services Wake-Up Call

To understand the scale of what's headed toward the industry, look at what major financial institutions are doing right now. These aren't organizations known for panic spending—they're methodical, risk-averse, and extremely good at calculating return on investment.

They're spending hundreds of millions of dollars on device management.

What triggered this massive spending? Specific regulatory requirements from agencies like the New York Department of Financial Services (NYDFS). By November 1, 2025, NYDFS will require organizations to "develop and maintain a comprehensive asset inventory of their information systems that includes key information tracking (e.g, owner, location, etc), policies for updating the asset inventory, and the procedure for disposing of information."

Joe Gaspardone, COO of Montgomery Technologies, puts this in broader context: "For the first time you've got compliance—we all knew this was going to come, but this is the first wave. NIST has released OT compliance standards."

The significance isn't just the new requirements—it's that compliance has never extended to building systems before. As Gaspardone explains, "When you're a publicly traded company or just a large private REIT, you are always doing compliance, and nothing has ever dipped down into the building. It's always been compliance at the organizational level, at the corporate level."

The liability is clear: "If you don't have control, and you don't have device management, you don't understand what you have, and ensuring that it's locked down, there's liability there."

This extends traditional IT asset management beyond corporate systems to operational technology in buildings. "Now they're coming back and saying you actually need to do this on all communicating devices that you have, including the building side. That's a massive change," White explains.

Here's what a comprehensive device remediation program looks like when regulators give you 90 days to fix compliance issues:

Full inventory of every networked device. Not just the big equipment—every controller, switch, and access point. Teams are literally crawling through telecom closets with clipboards and barcode scanners.

Classification of each device's cybersecurity posture. What firmware version is running? When was it last patched? What vulnerabilities are exposed? As White notes, "When they do a full IT asset management inventory, they want to know everything about the device; whether or not it's end-of-life or not, or if it's ever been upgraded, patched, maintained; everything related to it."

Programmatic approach to ongoing lifecycle management. This isn't a one-time audit. It's building the infrastructure to track and maintain thousands of devices across global portfolios.

The spending is massive precisely because they waited. These institutions are discovering devices that have been unmanaged for years, with legacy junk partially protected when barriers are built around the mess as a stop gap. The cost to remediate years of unmanaged devices and bring them into compliance is staggering.

But here's the thing—they have to do it, and fast. The alternative is facing regulatory penalties that could make the remediation costs look modest.

Why This Matters Beyond Financial Services

The regulatory pressure hitting banks is just the leading edge. White predicts the federal government will "continue to try to push this from beyond financial services to this should be a best practice that everyone is doing." The reasoning is stark: building infrastructure is "seen as one of the largest national security threats from a cyber perspective" because so much of it is legacy, lacks secure design and implementation by vendors who often do not have proper training or understanding of cyber best practices.

But compliance is only one driver. There are other forces making device management unavoidable:

Cybersecurity threats are escalating. Recent data shows building automation protocols are increasingly targeted in OT attacks, with building automation rising from 1% to 9% of all operational technology attacks in just one year. According to TXOne Networks, when a building automation engineering firm in Germany lost "control of many field devices (such as light switches, motion detectors, shutter controllers)" it led to a cyberattack in 2021, it wasn't an isolated incident—it was a preview of what's coming.

Smart building use cases depend on device reliability. Every sensor that goes offline breaks something else. Building owners are discovering this across multiple applications. As James Hare, a building systems specialist with ARUP, notes when discussing fault detection and diagnostics (FDD), "if you don't control the settings on those devices, you can then roll back all of your good work on your FDD optimizations."

But the dependencies extend far beyond energy analytics. There are two distinct challenges: devices that pass data to enable smart building use cases, and devices that simply need to be maintained to fulfill their basic function.

Rick Szcodronski, Chief Product Officer at Willow, describes the first category—devices that feed data to other systems. One client discovered they had "eight different IoT solutions" across their campus that needed management as "truly managed assets," from occupancy sensors that feed space utilization analytics to remote IoT sensor monitoring.

The second category includes devices that require ongoing maintenance and connectivity just to work as intended. Workplace equipment like connected fitness machines, AV systems in conference rooms, and smart appliances all depend on reliable network access to deliver their core functionality. As White explains, the goal is often ensuring building teams are "the ones finding out that there's an issue before the occupant does."

In both cases, device management failures have immediate operational impact—either breaking the data flows that power smart building insights or preventing basic building amenities from functioning properly.

The pattern is consistent: smart building applications fail when the underlying devices aren't properly discovered, classified, and maintained.

Insurance companies are taking notice. White reports seeing "insurance companies now looking at this program and saying, 'Wow, these are awesome programs that you guys are building. We would like to take these programs and recommend them out to our portfolio of owners, because this minimizes so much risk.'"

Competitive pressure is building. White predicts a future where device management becomes a differentiator between properties. For new developments, he sees an opportunity: "If I was a developer doing new properties, I would get this in place right away and say, I'm giving you an infrastructure that you will not have to worry about in five years."

The competitive dynamic may emerge as corporate tenants become more aware of how infrastructure affects their own technology initiatives. Companies facing massive remediation costs in their current buildings could eventually prioritize locations where device management is already solved, rather than inheriting someone else's technical debt.

The tsunami isn't just regulatory—it's economic, competitive, and operational.

What Device Management Actually Means

Most building owners think they're already doing device management. They're not. As Hare observes, "The vast majority of clients outside of certain industries are not really aware of this stuff. They have their BMS systems running. They have a contractor maintaining them." Gaspardone describes the common mindset: "Everybody thinks somebody else is responsible for this solution... about at least about half the time, maybe probably more, they think that they have it."

What they're actually doing is reactive maintenance—hoping their BMS contractor shows up when something breaks while assuming their IT vendor handles network security.

Real device management is a program, not a project. It has six components:

1. Discovery: What Devices Exist?

This is the literal dirty job. Gaspardone describes sending teams into telecom closets to "unravel a plate of spaghetti into clean lines that are intelligible." The process involves documenting every piece of equipment, its network infrastructure, understanding its purpose, and mapping connections that often lack proper labeling.

Hare explains Arup's approach, which combines physical inspections with network-based scanning for devices. But regardless of method, teams face the same underlying problem: "Documentation is not present. No one knows where the drawings live. No one has the right vendor contact... It's the wild wild west."

2. Assessment: What's Their Cybersecurity Posture?

Discovery reveals what devices exist, but assessment determines their security status. This means identifying firmware versions, patch histories, and whether devices appear on lists of known vulnerabilities. Some building owners work with technology partners to enrich this process—Willow, for example, integrates with Mapped, an independent data layer provider, to enhance device discoveries during network scans by identifying firmware versions and exposed devices.

Building owners often discover their systems have been neglected for years—firewalls that haven't been updated in a decade, BAS systems wide open to the internet.

3. Classification: How Do Devices Relate to Operations?

Moving beyond basic inventories requires understanding how devices connect to actual building operations. The challenge is visualizing relationships that aren't obvious from device lists alone. As Szcodronski explains, "Something as simple as a piece of HVAC equipment... has on average, in our Knowledge Graph, eight to 12 relationships."

That single piece of equipment isn’t just a line item—it’s tied to the room it sits in, the upstream and downstream equipment it depends on, the controller that operates it, the network that controller sits on, and the spaces it heats, cools, or ventilates. Each relationship creates dependencies that must be tracked if owners want a truly accurate picture of their building operations.

Some building owners are moving beyond Excel spreadsheets toward data layers—digital systems that can map these complex relationships between devices, equipment, and spaces. Whether built in-house or purchased from vendors like Willow, these platforms replace static spreadsheets with living, connected views of how assets relate. The approach varies—some use knowledge graphs, others rely on structured databases—but the common goal is the same: moving beyond a simple list of devices toward a system that shows how those devices actually work together in the building.

Data layer platforms add value across multiple phases of device management. They support discovery and assessment by unifying the raw device list (the asset register) with a knowledge graph that shows how each piece of equipment connects to controllers, networks, and spaces. They also help with classification by standardizing how devices are named and organized, avoiding the confusion of inconsistent labels across portfolios.

But their value extends far beyond device management—by combining asset registers and knowledge graphs with real-time data streaming from the building, they enable operational use cases ranging from energy optimization to predictive maintenance. As Szcodronski explains, 'Teams used to spend hours—sometimes a whole day—digging through old drawings or thumb drives to figure out how equipment was connected. With the knowledge graph, you get that answer in seconds.'"

4. Remediation: How Do You Fix the Problems?

Building owners take different approaches to fixing what they find. Some work with consultants to write specifications and manage multiple contractors through a bidding process. For example, ARUP often helps owners by scoping the work in detail, so local contractors can bid and execute under the owner’s oversight. This model gives owners flexibility and control, but also requires them to coordinate multiple vendors and ensure accountability.

Others prefer end-to-end service providers who handle both design and execution of converged networks. Montgomery Technologies, for instance, takes a turnkey approach—writing the specification, executing the work, and managing the network lifecycle as a managed service. For owners without the internal resources to manage multiple contractors, this one-stop-shop model reduces complexity and transfers more responsibility to the provider.

The remediation approach often depends on the building owner's internal capabilities, budget, and timeline. But the goal is consistent: creating managed, segmented networks where access is controlled and systems are properly integrated.

5. Maintenance: How Do You Keep Records Current?

This is where most programs fail. The challenge isn't just cleaning up the existing mess—it's preventing a return to chaos. Some building owners implement automated platforms for firmware management at scale, while others rely on structured manual processes with regular audit cycles.

As Gaspardone points out, buildings are constantly changing, and unmanaged networks deteriorate quickly: “You walk in eight years later, and there’s the firewall, and it’s exactly in the state it was when it was installed. There’s no subscription, there’s no updating, there’s nothing.”

The key insight from successful programs is establishing ongoing processes to prevent falling back into disorder, whether through technology solutions, service contracts, or internal procedures.

6. Setting Standards for Future Devices

The final piece—often overlooked—is establishing requirements for what devices can be installed going forward. As White notes, just selecting "open devices isn't enough anymore”. Smart device selection spends capital efficiently by considering the full lifecycle and avoids creating problems that require additional resources down the road.

The Stakeholder Gap: Who Owns This Problem?

Here's why device management problems persist: nobody owns them. In most organizations, device management falls into a gap between multiple stakeholders who all assume someone else is handling it.

IT Teams see operational technology as outside their scope, focusing instead on corporate systems. In higher education and healthcare, where IT teams do engage with building systems, they often treat OT equipment like traditional IT assets, creating bureaucratic barriers that can slow building projects.

Facilities Teams are often focused on the immediate needs of building operations—keeping occupants comfortable, responding to hot and cold calls, and ensuring systems stay online. In that environment, it’s easy for long-term considerations like firmware updates or cybersecurity to take a back seat. As Matt White explains, facility managers make day-to-day equipment decisions that solve urgent problems, but those choices can have ripple effects for years to come, depending on the devices they select and the contractors they engage.

Construction Teams install devices during the build phase, then move on to the next project without any ongoing lifecycle responsibility. Everything gets delegated to low-bid contractors with no standards for network infrastructure and often leave little in the way of operational documentation or standards for device management.

Vendors and Service Providers are incentivized to avoid this responsibility entirely. The business model doesn't support it. As White explains, major facility management companies "refuse to put the contractual language on their side of anything related to cyber security, or networks. They will not do it. Their lawyers will not let them" except for special negotiations with top-tier clients. The liability exposure is too high and the expertise requirements too specialized for companies built around traditional building maintenance and service contracts.

Executives assume someone in the organization has device management covered. As Gaspardone explains, "Everybody thinks somebody else is responsible for this solution." Property managers assume corporate IT handles it, while IT assumes facilities management does.

The result: nobody raises their hand until compliance requirements or a security incident forces action. By then, the remediation costs are massive because the problem has been growing unmanaged for years. And if a security incident occurs first, the financial damage extends far beyond remediation. The hard costs of a data breach in the financial sector is in the millions. That's before accounting for operational downtime, regulatory fines, customer losses, and reputational damage that can take years to recover.

The Path Forward: Lessons for Building Owners

Assign ownership. Organizations need to decide which department will take responsibility for this challenge. Some, like Google, have expanded their network management teams to include OT devices alongside corporate IT. Others hire managed service providers or consultants to fill the gap.

Start budgeting now. As White warns, the timeline for addressing device management is longer than most building owners realize. By the time you understand what you have and develop a remediation plan, spreading those costs across multiple (read: 5 or more) budget cycles becomes essential. Waiting makes the problem exponentially more expensive.

Right-size your approach. The solution depends on your portfolio size and capabilities. Smaller building owners can implement structured manual inventories every six to twelve months, combined with clear standards for future device installations. Larger portfolios benefit from automated discovery tools and managed service providers who can execute consistently across multiple buildings.

Start with visibility. Understanding what devices you have is the foundational step, even if that information initially lives in a simple database that won't become immediately obsolete.

Don't wait for compliance to force action. Organizations moving proactively can spread costs across multiple budget cycles and avoid the emergency spending that financial institutions are experiencing now.

Use vendor partners where internal capacity doesn't exist. As Hare notes, unless you have a global company with this capability in-house, "it makes more sense to contract it out to service providers to help you get to that place."

Some building owners are turning to managed service providers to bridge the staffing gap entirely. Gaspardone's company, Montgomery Technologies, offers a service called Intelligent Riser for commercial office and multifamily owners, where they supplement the owner's lack of OT staff and perform device management on their behalf for a monthly fee. This approach recognizes that many building owners simply don't have—and may never have—the internal expertise to manage this problem themselves.

Recognize this is an ongoing program, not a one-time project. The goal isn't just cleaning up the existing mess—it's building systems and processes to prevent falling back into chaos.

The Competitive Reality

White's prediction cuts to the heart of why this matters: "A typical building owner may not yet have to be as aggressive as regulated institutions, but they should be afraid of the tsunami that's coming and start addressing it now."

Device management is no longer a nice-to-have. The mix of regulatory pressure, cybersecurity concerns, and operational dependencies means it’s becoming an expectation. Financial institutions are spending heavily because they waited, but not every owner will experience the same emergency timeline.

For most, the smart move is to assess your own level of risk and start planning accordingly. Acting now gives organizations the chance to spread costs across budget cycles, assign ownership, and build sustainable processes. Waiting often leads to compressed timelines and higher costs—but the scale and urgency depend on your portfolio, your systems, and your regulatory exposure.

Importantly, this isn’t just about compliance or risk avoidance. Building owners who put programs in place are better positioned to deliver on the smart building promises that many talk about but few achieve—fault detection that actually works, energy optimization that sticks, and systems that operate as intended.

Every month of delay shortens your runway, but starting now means you can move at a pace that matches your own risk profile and organizational priorities.

---

Keep Reading Links:

Marketplace helps you find network managers and consultants, data layer providers, and more

NexusCon '24 session on this topic.

Summary article on above session.

This is a great piece!

I agree.