Your HVAC service contract is up for renewal. The familiar ritual begins: your contractor sends over the same proposal from last year with a modest price increase. Four quarterly visits. Filter changes. Visual inspections. A long checklist of scheduled tasks performed whether your building needs them or not.

This approach worked for decades when buildings were simpler and technology was limited. But the landscape has shifted dramatically.

While many building owners continue signing predictable service agreements, a quiet transformation is reshaping how the most proactive organizations approach maintenance. Instead of paying for hours and hoping for results, they're partnering with providers who focus on outcomes. Instead of scheduled tasks performed regardless of need, they're getting data-driven insights that prevent problems before they start.

The shift is from billing time to billing results—and it represents the biggest change in building services in generations.

For decades, the building service industry operated on a simple premise: charge for time, perform scheduled tasks, respond to problems. The typical maintenance contract looked like a restaurant menu—predictable items at predictable prices, regardless of whether you needed them.

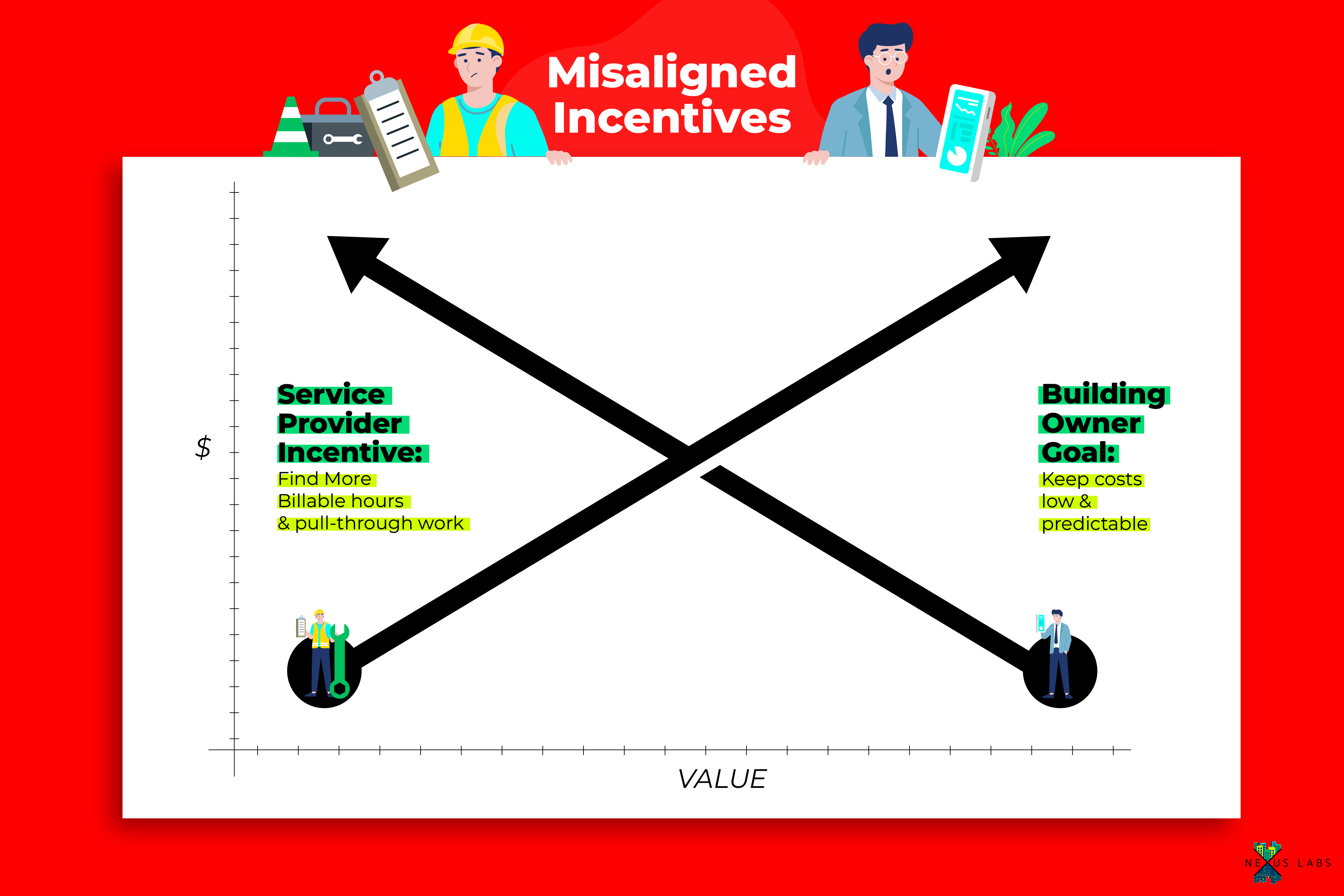

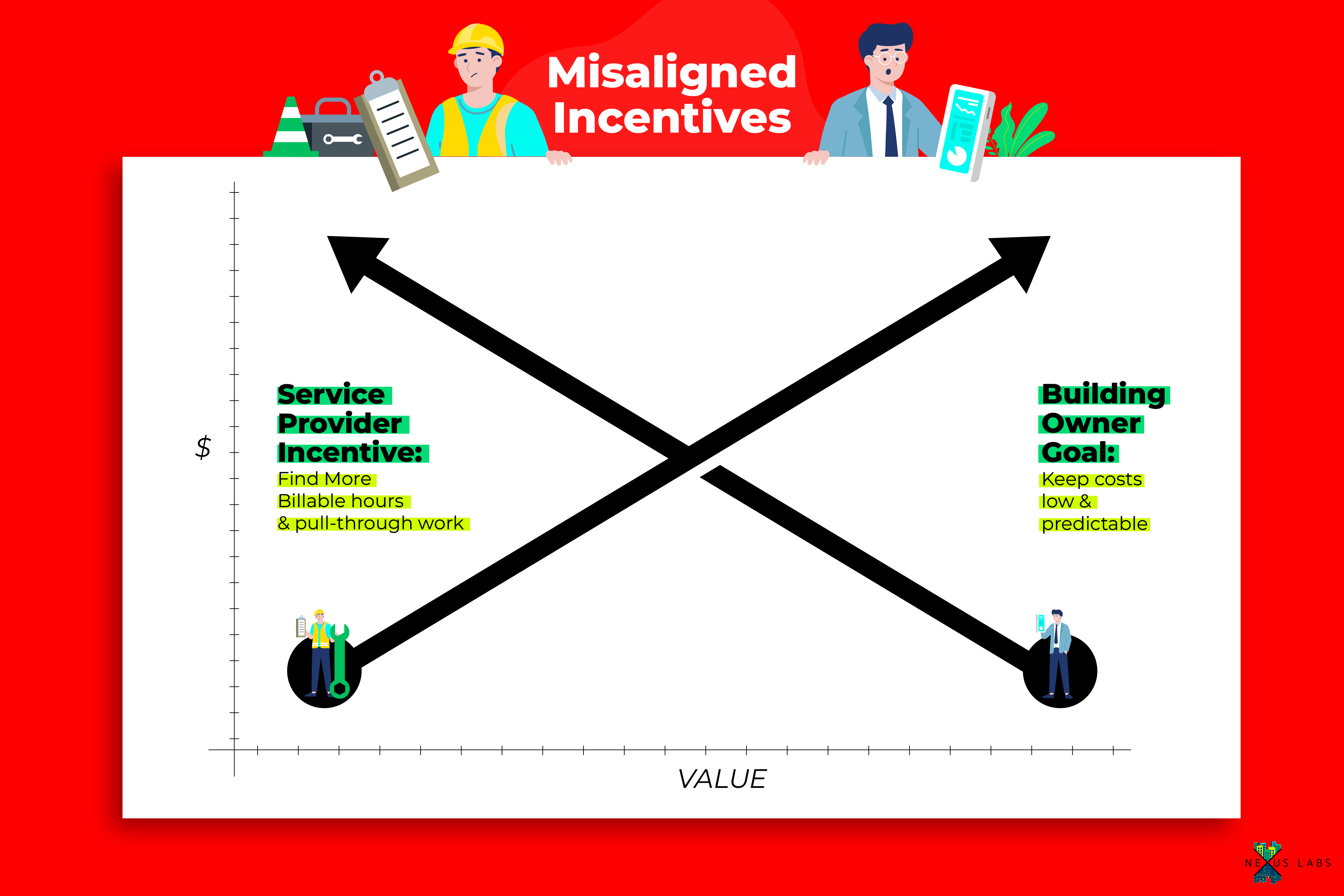

This model misaligned incentives between the building owner and vendor. When service providers billed by the hour, financial success came from more billable time rather than optimal building performance. Building owners wanted efficient, reliable operations at predictable costs. Service providers needed sufficient billable hours to maintain profitability.

These goals often worked against each other.

Service providers often rely on what they term "pull-through work"—additional repairs discovered during routine visits. Finding problems during inspections meant opportunities for additional revenue. Meanwhile, building owners struggled with unpredictable costs. The base service contract might cover routine tasks, but anything beyond the prescribed checklist triggered time-and-materials charges. A simple quarterly visit could expand into significant unexpected expenses, with limited visibility into whether the additional work was essential or could have been prevented.

Tim Cramer from Clockworks Analytics highlights the misalignment of incentives by describing what a bad traditional service engagement looks like and why it happens: "If I get called out four times for the same problem, because it took me four tries to solve it, and I have the T&M meter running every single time, and I'm making the money every time I get called out, I increased my pull-through work," notes Cramer. "It's clearly not a better experience for the customer to have to call you back out four times, but I got paid four times over."

This created a transparency challenge. Building owners had limited insight into whether their maintenance investments were optimizing performance or simply meeting contractual obligations.

Building analytics platforms have been available for over a decade, but most service providers still operate without them.

The barrier hasn't been technology—it's been business model confusion.

Most service providers initially tried to sell analytics platforms as separate products to building owners, requiring customers to buy, manage, and interpret complex software themselves.

The shift started when some contractors realized they didn't need their customers to buy the software. They could use it internally to deliver better service.

"Platforms like Clockworks have been available for a dozen years now," explains Brian Turner from OTI, a master systems integrator. "Contractors like MacDonald-Miller are just the first ones to recognize that it's their tool. It's not their customers'. It's not the whole sales cycle of 'my customer won't buy it.' It's like you're a service provider. Did you ask them to buy your drill for you?"

The result: service providers could finally treat technology as practical tools rather than experimental products.

Not all service providers are moving at the same pace. The transformation follows a predictable pattern across five distinct stages.

Stage 0: Status Quo Most contractors remain here: scheduled preventive maintenance, reactive service calls, billing by the hour. Tasks are performed whether needed or not. Building owners receive little data beyond basic work orders.

Stage 1: Technology Curiosity Contractors attend demos, run small pilots, but haven't committed to systematic change. They might use FDD on a few buildings but haven't integrated it into their core service delivery. The technology remains separate from their day-to-day operations.

Stage 2: Technology-Enabled Recordkeeping This represents the first meaningful step forward. Contractors begin maintaining detailed digital asset registries, tracking repair costs by equipment, and providing customer portals with basic performance data.

Stage 3: Outcome-Based Maintenance Contractors begin defining and reporting on outcomes: comfort scores, energy efficiency metrics, avoided costs. They shift from "we changed 150 filters" to "we maintained 98% comfort score while reducing energy use by 12%."

Stage 4: Condition-Based Maintenance This stage requires continuous monitoring technology to optimize when and how maintenance occurs. Instead of quarterly filter changes regardless of need, technicians respond to actual equipment conditions based on real-time data.

Stage 5: Full Outcome-Based Billing (Future State) The most mature stage—still largely theoretical—involves charging based on actual results: equipment longevity, energy savings, avoided downtime. Service providers become true partners, sharing in the economic outcomes they help create.

The progression from recordkeeping to outcome-based service represents a significant operational shift. "I think some of the easier steps you can take in the beginning is being technology-enabled, but in the way of helping to be the system of record for their mechanical assets," explains Reed Powell from MacDonald-Miller. "The portal that we are providing does not require really anything outside of the norm for a provider—you just have to start collating all that data together."

Moving into condition-based maintenance requires more sophisticated integration. "Another powerful way to present it or show value is our technicians have access to [FDD] as well, so they can go in and find the nine most recent anomalies," explains Steve Adams from MacDonald-Miller. "It gives them an area to focus their time. Instead of going and looking at 90 VAV boxes through the course of a week, we might be able to go through the FDD, find nine little areas that had an issue, and that kind of focuses our time."

The most advanced stage remains largely theoretical. Tim Cramer from Clockworks describes the vision: "If I can accurately compute for you all the money that I saved you in a year, I am charging you some percentage of that because then it's win-win. I'm making money because I am providing an excellent service. You're saving overall because of the service that I'm providing."

One of the largest service providers west of the Mississippi, MacDonald-Miller operates at Stage 4, demonstrating how condition-based maintenance works in practice. The company has built custom dashboards in PowerBI integrated with Clockworks' analytics platform, providing customers with performance metrics and avoided cost calculations.

"We've been doing this for 10 years," explains Reed Powell from MacDonald-Miller. "It's been building momentum within our leadership teams."

When clients question renewal decisions, the company could demonstrate specific value: "Here's your smart building services dashboard. Here's where I can show you all the costs that you've avoided this year because of our service," recalls Tim Cramer from Clockworks. "Here's where I can show you that your indoor environmental quality score is 98%, that you're operating in optimal efficiency."

But MacDonald-Miller's sophistication also highlights the industry's core problem: there simply aren't enough MacDonald-Millers serving the market.

"The vast majority of service contractors out there just are not going to build that capability," explains Brian Turner. "They're not going to have the stamina for it. They're not going to have the cash flow for it, and in a lot of cases, the desire to do it right. They want to be mechanics. They provide huge value for buildings, but the reality is they're just not equipped to do the job the way it needs to be done today."

This scarcity has created opportunities for companies like OTI, which positions itself as providing "the level of service that MacDonald-Miller has built in-house to a less sophisticated technical audience."

OTI's remote operations model (launching in late 2025) allows smaller contractors to access enterprise-level analytics and expertise without building internal capabilities. OTI buys enterprise software licenses, analyze building data centrally, and dispatch appropriate service providers based on actual equipment needs rather than predetermined schedules.

"We can dispatch these 10 service providers to the same problem across 10 different properties. Then show how they ranked in their ability to understand and diagnose and complete the issue," Turner explains.

The model solves the fundamental challenge: most service providers lack the resources to hire dedicated smart buildings experts, but their customers increasingly expect data-driven service.

The transformation creates both opportunity and risk for building owners. Those who understand the new landscape can drive better outcomes and more predictable costs. Those others risk being stuck with outdated service models while their competitors gain operational advantages.

The core challenge: many building owners don't yet know these services exist.

"It's very rare for us to run into an owner who is proactive enough to be asking about the technology-enabled service provider," Powell reports. "We are doing most of the market education."

This puts building owners in a reactive position precisely when they should be driving the conversation. The next time your service contract comes up for renewal, here's what to look for and ask.

Clear accountability metrics. Do they offer specific performance indicators: comfort scores, energy efficiency ratings, avoided maintenance costs, equipment longevity metrics. If they can't show you how they measure success beyond hours worked, find someone who can.

Experience with technology-enabled maintenance. Ask directly: "How many other clients do you serve using this model?" If you're ground zero for their technology experiment, you'll bear the costs of their learning curve.

Transparency through data. Think: customer portals showing real-time building performance, maintenance histories, and predictive insights. "How are your current providers grading themselves?" Powell asks prospects. "How are they holding themselves accountable to the outcomes of their contract?"

Flexible contract structures. Are they willing to work with you to adjust maintenance frequency based on actual equipment conditions and risk tolerance? "Do they provide things like a comfort score or an energy efficiency score? Do they have any ways to reduce visual inspections and do those with technology?" Powell suggests asking.

Arbitrary KPIs. Contracts that measure success by "less than 30 alarms per week" or "less than 40 cold calls per month" optimize for the wrong outcomes. These metrics encourage reactive fixes rather than proactive optimization.

Prescriptive task lists. Beware contracts that specify exactly what will be done over the next 365 days without regard to actual building needs. "How do I know what we're going to do?" Powell asks. "I don't even know what your buildings are doing yet."

Lack of cost visibility. Traditional contracts often provide little insight into repair costs by equipment, maintenance trends, or capital planning support. Technology-enabled service providers help you understand your building as a managed asset.

The most revealing questions for service providers focus on outcomes and accountability:

If a provider can't give specific, data-backed answers to these questions, they're probably still operating in the old model.

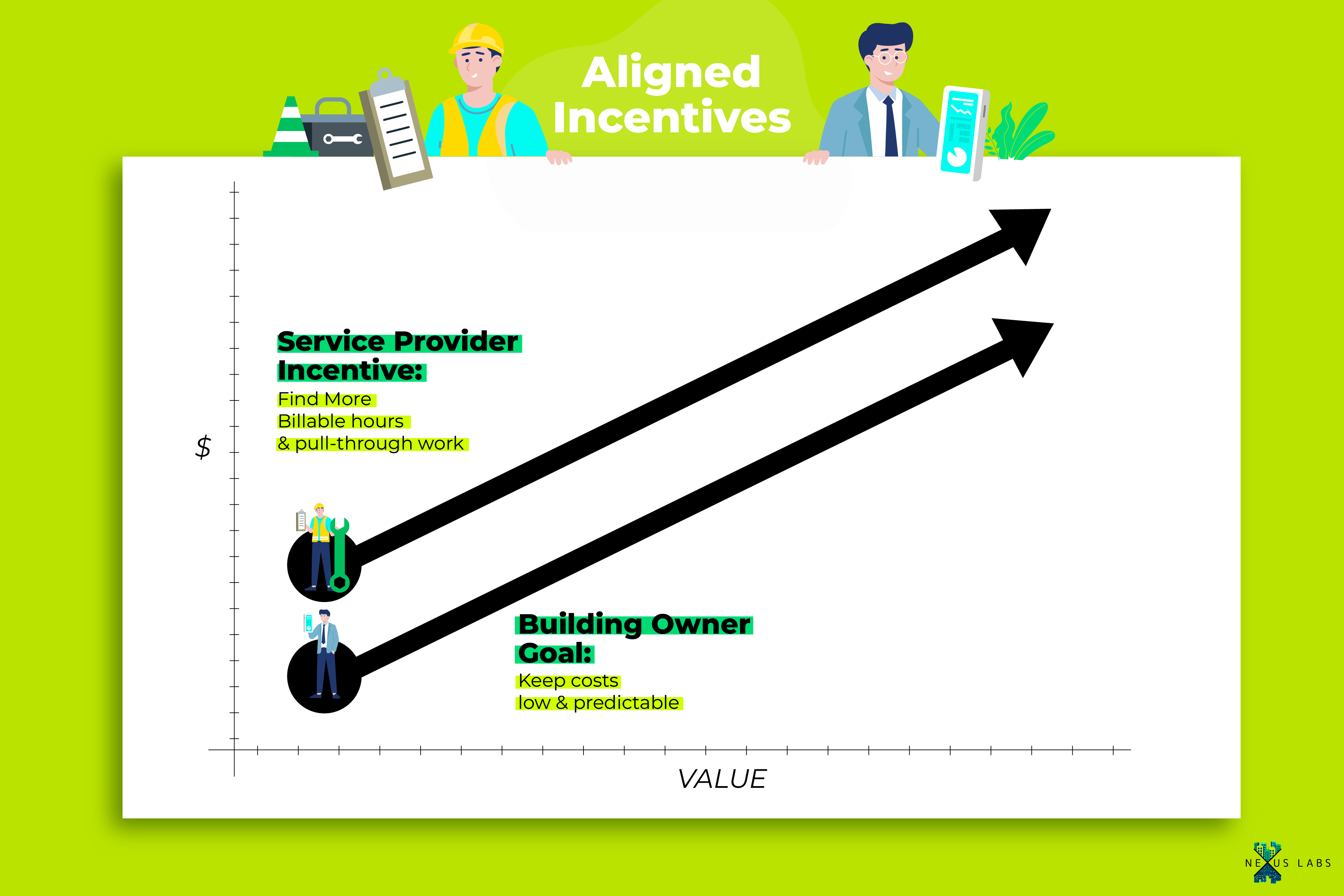

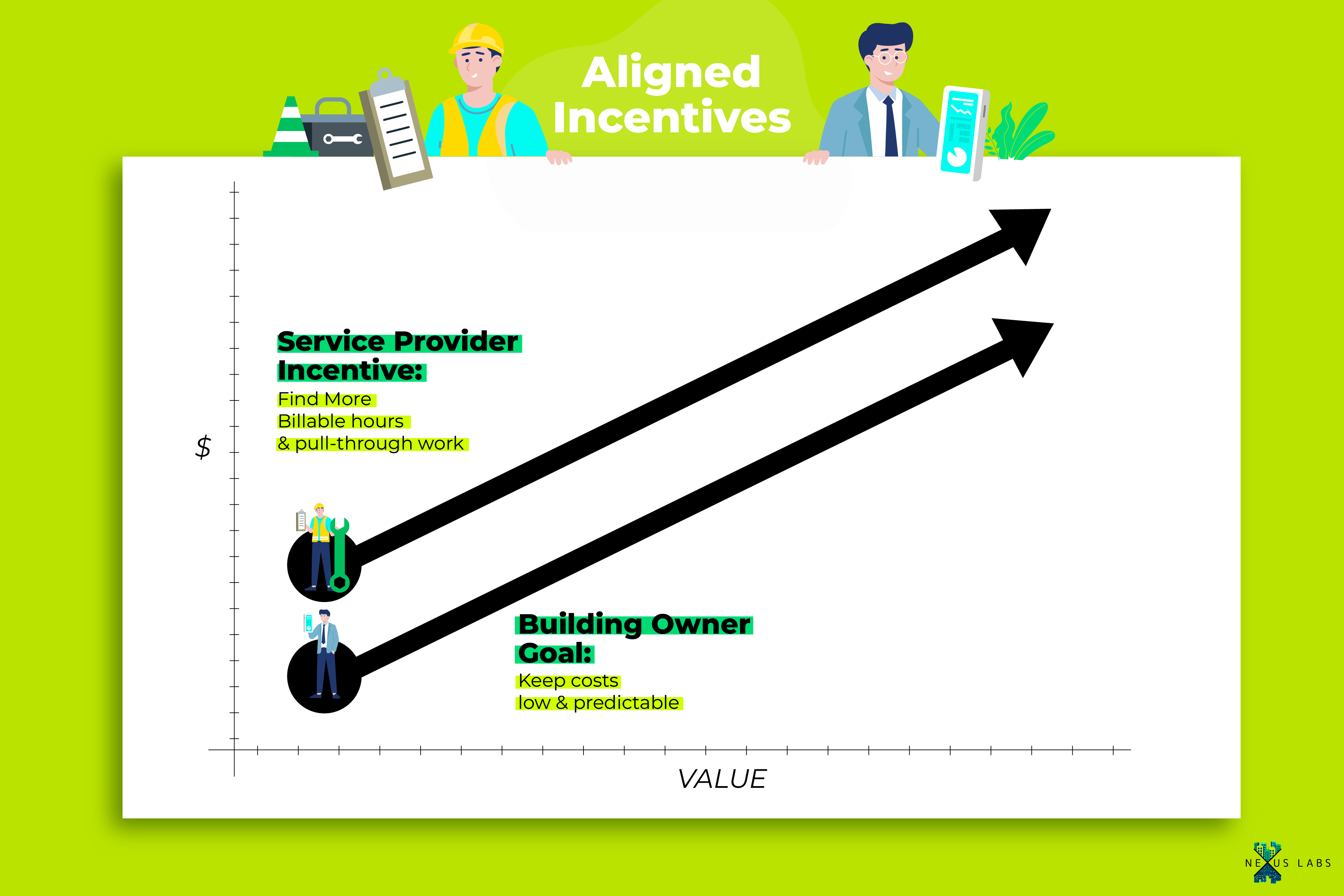

The most profound change isn't technological—it's economic. Technology-enabled services finally align the interests of building owners and service providers in ways the traditional model never could.

Under the old system, service providers made more money when equipment failed or when maintenance took longer than expected. Building owners wanted reliable, efficient operations at predictable costs. These goals were fundamentally at odds.

Technology changes this dynamic by making value visible and quantifiable. When service providers can demonstrate avoided costs, energy savings, and extended equipment life, they can justify premium pricing based on results rather than hours.

"It's not more profitable for us, but it's the right thing to do if we want to work with our clients long term," Powell explains. "You also don't want to end up one day waking up to [companies like] Cushman Wakefield sending out Uber driver-style requests for an HVAC call, and you're just scrambling to respond first at the lowest price."

This shift has practical implications for contract structure and budgeting:

More predictable costs. Technology-enabled monitoring reduces surprise failures and emergency repairs. Building owners can budget more accurately when maintenance is driven by actual equipment conditions rather than arbitrary schedules.

Shared risk and reward. Advanced contracts might include provisions where service providers share in energy savings or receive bonuses for extended equipment life. This creates incentives for optimization rather than just maintenance.

Reduced administrative overhead. Automated monitoring and reporting reduce the management burden on building owners while providing better visibility into building performance.

The transformation also enables new service delivery models. Remote operations centers can monitor multiple buildings 24/7, dispatching technicians only when needed and arriving with specific diagnostic information and appropriate parts.

Despite the progress in data collection and analysis, a critical operational challenge prevents many service providers from fully embracing condition-based maintenance: their work order systems can't handle flexible, data-driven scheduling.

Most maintenance management software was built for the old model—scheduled tasks that happen regardless of need. These systems struggle with the dynamic decision-making that condition-based maintenance requires. When a building's data suggests that some equipment needs attention while other systems can wait, current software can't easily adjust schedules, bundle related work, or reallocate budget accordingly.

"The next biggest hurdle for making condition-based maintenance really work is [maintenance management] platforms," Powell explains. "There is no effective way for us to manage a flexible budget and bundle work orders and float PM tasks based on conditions of assets."

This creates a bottleneck for building owners. While the technology exists to identify what needs attention and when, translating those insights into efficient service delivery remains largely manual. Service providers need experienced personnel to make real-time decisions about work prioritization and resource allocation—a constraint that limits how quickly the industry can scale these approaches.

"You need someone who has many years of experience in the industry to do the right work order bundling and manage that budget for a customer," Powell notes. "So it's super clunky today."

For building owners, this means the full benefits of predictable, optimized maintenance remain partially unrealized. The ideal scenario—where building data seamlessly drives service decisions and budget allocation—requires better integration between monitoring platforms and operational workflows.

This limitation explains why the transformation remains in early stages and why companies like MacDonald-Miller represent exceptions rather than the rule.

Most service providers face significant barriers to adopting technology-enabled approaches: upfront software costs, the need for specialized staff, workflow system limitations, and uncertainty about return on investment.

But building owners don't have to wait for the entire industry to evolve. They can actively drive this transformation by changing how they approach service contract renewals and what they demand from providers.

Building owners ready to embrace technology-enabled services face a change management challenge as much as a procurement decision. The transition requires new ways of thinking about building operations, service relationships, and cost management—but it also represents an opportunity to gain competitive advantages while the majority of the market remains stuck in traditional models.

Start with your next renewal. Don't wait for contracts to expire—begin conversations early about shifting to outcome-based models. Give providers time to prepare new proposals that demonstrate value through data.

Define your outcomes. Be specific about what you want to achieve: energy reduction targets, comfort score improvements, reduced emergency repairs, extended equipment life. Vague goals produce vague results.

Invest in building data infrastructure. Technology-enabled services require connected building systems. If your building lacks adequate sensors or network connectivity, factor upgrade costs into your decision.

Plan for cultural change. Your facilities team may need training on new dashboards, reporting tools, and performance metrics. Budget time and resources for this transition.

Start with pilot programs. Consider testing technology-enabled services on a subset of buildings or systems before committing to organization-wide changes.

The transition isn't without risks. Early adopters may pay premium prices while the market matures. Technology integration can be complex, particularly in older buildings. And not all service providers claiming to offer tech-enabled services have the capabilities to deliver on their promises.

But the risks of not transitioning may be greater. As energy costs rise, sustainability mandates tighten, and building expectations increase, traditional service models become less viable. Building owners who wait may find themselves at a competitive disadvantage.

The transformation of building services represents a broader shift in how we think about building operations. Instead of treating mechanical systems as necessary expenses, forward-thinking owners are recognizing them as manageable assets that can drive competitive advantages.

"You're telling me you can't get rid of a service provider, because they dictate to you what needs to be done. They're the ones who know everything about the building," Turner challenges building owners. "You're not acting like you own this facility or that your mechanical systems are part of your asset that you actually own. You're acting like you're renting this from this service provider."

This mindset shift—from passive recipient to active partner—may be the most important outcome of technology-enabled services. When building owners have access to real-time performance data and clear accountability metrics, they can make informed decisions about maintenance priorities, capital investments, and operational strategies.

The technology exists. The service providers are evolving. The business models are emerging. What's missing is widespread adoption by building owners who understand their newfound leverage in these relationships.

Your next service contract renewal represents more than a routine procurement decision. It's an opportunity to fundamentally change how your building operates, how costs are managed, and how value is created.

The question isn't whether technology-enabled services will become the standard—it's whether you'll be an early adopter who shapes these relationships or a late follower who accepts whatever terms the market offers.

The choice, as they say, is yours. But the window for competitive advantage won't stay open forever.

Your HVAC service contract is up for renewal. The familiar ritual begins: your contractor sends over the same proposal from last year with a modest price increase. Four quarterly visits. Filter changes. Visual inspections. A long checklist of scheduled tasks performed whether your building needs them or not.

This approach worked for decades when buildings were simpler and technology was limited. But the landscape has shifted dramatically.

While many building owners continue signing predictable service agreements, a quiet transformation is reshaping how the most proactive organizations approach maintenance. Instead of paying for hours and hoping for results, they're partnering with providers who focus on outcomes. Instead of scheduled tasks performed regardless of need, they're getting data-driven insights that prevent problems before they start.

The shift is from billing time to billing results—and it represents the biggest change in building services in generations.

For decades, the building service industry operated on a simple premise: charge for time, perform scheduled tasks, respond to problems. The typical maintenance contract looked like a restaurant menu—predictable items at predictable prices, regardless of whether you needed them.

This model misaligned incentives between the building owner and vendor. When service providers billed by the hour, financial success came from more billable time rather than optimal building performance. Building owners wanted efficient, reliable operations at predictable costs. Service providers needed sufficient billable hours to maintain profitability.

These goals often worked against each other.

Service providers often rely on what they term "pull-through work"—additional repairs discovered during routine visits. Finding problems during inspections meant opportunities for additional revenue. Meanwhile, building owners struggled with unpredictable costs. The base service contract might cover routine tasks, but anything beyond the prescribed checklist triggered time-and-materials charges. A simple quarterly visit could expand into significant unexpected expenses, with limited visibility into whether the additional work was essential or could have been prevented.

Tim Cramer from Clockworks Analytics highlights the misalignment of incentives by describing what a bad traditional service engagement looks like and why it happens: "If I get called out four times for the same problem, because it took me four tries to solve it, and I have the T&M meter running every single time, and I'm making the money every time I get called out, I increased my pull-through work," notes Cramer. "It's clearly not a better experience for the customer to have to call you back out four times, but I got paid four times over."

This created a transparency challenge. Building owners had limited insight into whether their maintenance investments were optimizing performance or simply meeting contractual obligations.

Building analytics platforms have been available for over a decade, but most service providers still operate without them.

The barrier hasn't been technology—it's been business model confusion.

Most service providers initially tried to sell analytics platforms as separate products to building owners, requiring customers to buy, manage, and interpret complex software themselves.

The shift started when some contractors realized they didn't need their customers to buy the software. They could use it internally to deliver better service.

"Platforms like Clockworks have been available for a dozen years now," explains Brian Turner from OTI, a master systems integrator. "Contractors like MacDonald-Miller are just the first ones to recognize that it's their tool. It's not their customers'. It's not the whole sales cycle of 'my customer won't buy it.' It's like you're a service provider. Did you ask them to buy your drill for you?"

The result: service providers could finally treat technology as practical tools rather than experimental products.

Not all service providers are moving at the same pace. The transformation follows a predictable pattern across five distinct stages.

Stage 0: Status Quo Most contractors remain here: scheduled preventive maintenance, reactive service calls, billing by the hour. Tasks are performed whether needed or not. Building owners receive little data beyond basic work orders.

Stage 1: Technology Curiosity Contractors attend demos, run small pilots, but haven't committed to systematic change. They might use FDD on a few buildings but haven't integrated it into their core service delivery. The technology remains separate from their day-to-day operations.

Stage 2: Technology-Enabled Recordkeeping This represents the first meaningful step forward. Contractors begin maintaining detailed digital asset registries, tracking repair costs by equipment, and providing customer portals with basic performance data.

Stage 3: Outcome-Based Maintenance Contractors begin defining and reporting on outcomes: comfort scores, energy efficiency metrics, avoided costs. They shift from "we changed 150 filters" to "we maintained 98% comfort score while reducing energy use by 12%."

Stage 4: Condition-Based Maintenance This stage requires continuous monitoring technology to optimize when and how maintenance occurs. Instead of quarterly filter changes regardless of need, technicians respond to actual equipment conditions based on real-time data.

Stage 5: Full Outcome-Based Billing (Future State) The most mature stage—still largely theoretical—involves charging based on actual results: equipment longevity, energy savings, avoided downtime. Service providers become true partners, sharing in the economic outcomes they help create.

The progression from recordkeeping to outcome-based service represents a significant operational shift. "I think some of the easier steps you can take in the beginning is being technology-enabled, but in the way of helping to be the system of record for their mechanical assets," explains Reed Powell from MacDonald-Miller. "The portal that we are providing does not require really anything outside of the norm for a provider—you just have to start collating all that data together."

Moving into condition-based maintenance requires more sophisticated integration. "Another powerful way to present it or show value is our technicians have access to [FDD] as well, so they can go in and find the nine most recent anomalies," explains Steve Adams from MacDonald-Miller. "It gives them an area to focus their time. Instead of going and looking at 90 VAV boxes through the course of a week, we might be able to go through the FDD, find nine little areas that had an issue, and that kind of focuses our time."

The most advanced stage remains largely theoretical. Tim Cramer from Clockworks describes the vision: "If I can accurately compute for you all the money that I saved you in a year, I am charging you some percentage of that because then it's win-win. I'm making money because I am providing an excellent service. You're saving overall because of the service that I'm providing."

One of the largest service providers west of the Mississippi, MacDonald-Miller operates at Stage 4, demonstrating how condition-based maintenance works in practice. The company has built custom dashboards in PowerBI integrated with Clockworks' analytics platform, providing customers with performance metrics and avoided cost calculations.

"We've been doing this for 10 years," explains Reed Powell from MacDonald-Miller. "It's been building momentum within our leadership teams."

When clients question renewal decisions, the company could demonstrate specific value: "Here's your smart building services dashboard. Here's where I can show you all the costs that you've avoided this year because of our service," recalls Tim Cramer from Clockworks. "Here's where I can show you that your indoor environmental quality score is 98%, that you're operating in optimal efficiency."

But MacDonald-Miller's sophistication also highlights the industry's core problem: there simply aren't enough MacDonald-Millers serving the market.

"The vast majority of service contractors out there just are not going to build that capability," explains Brian Turner. "They're not going to have the stamina for it. They're not going to have the cash flow for it, and in a lot of cases, the desire to do it right. They want to be mechanics. They provide huge value for buildings, but the reality is they're just not equipped to do the job the way it needs to be done today."

This scarcity has created opportunities for companies like OTI, which positions itself as providing "the level of service that MacDonald-Miller has built in-house to a less sophisticated technical audience."

OTI's remote operations model (launching in late 2025) allows smaller contractors to access enterprise-level analytics and expertise without building internal capabilities. OTI buys enterprise software licenses, analyze building data centrally, and dispatch appropriate service providers based on actual equipment needs rather than predetermined schedules.

"We can dispatch these 10 service providers to the same problem across 10 different properties. Then show how they ranked in their ability to understand and diagnose and complete the issue," Turner explains.

The model solves the fundamental challenge: most service providers lack the resources to hire dedicated smart buildings experts, but their customers increasingly expect data-driven service.

The transformation creates both opportunity and risk for building owners. Those who understand the new landscape can drive better outcomes and more predictable costs. Those others risk being stuck with outdated service models while their competitors gain operational advantages.

The core challenge: many building owners don't yet know these services exist.

"It's very rare for us to run into an owner who is proactive enough to be asking about the technology-enabled service provider," Powell reports. "We are doing most of the market education."

This puts building owners in a reactive position precisely when they should be driving the conversation. The next time your service contract comes up for renewal, here's what to look for and ask.

Clear accountability metrics. Do they offer specific performance indicators: comfort scores, energy efficiency ratings, avoided maintenance costs, equipment longevity metrics. If they can't show you how they measure success beyond hours worked, find someone who can.

Experience with technology-enabled maintenance. Ask directly: "How many other clients do you serve using this model?" If you're ground zero for their technology experiment, you'll bear the costs of their learning curve.

Transparency through data. Think: customer portals showing real-time building performance, maintenance histories, and predictive insights. "How are your current providers grading themselves?" Powell asks prospects. "How are they holding themselves accountable to the outcomes of their contract?"

Flexible contract structures. Are they willing to work with you to adjust maintenance frequency based on actual equipment conditions and risk tolerance? "Do they provide things like a comfort score or an energy efficiency score? Do they have any ways to reduce visual inspections and do those with technology?" Powell suggests asking.

Arbitrary KPIs. Contracts that measure success by "less than 30 alarms per week" or "less than 40 cold calls per month" optimize for the wrong outcomes. These metrics encourage reactive fixes rather than proactive optimization.

Prescriptive task lists. Beware contracts that specify exactly what will be done over the next 365 days without regard to actual building needs. "How do I know what we're going to do?" Powell asks. "I don't even know what your buildings are doing yet."

Lack of cost visibility. Traditional contracts often provide little insight into repair costs by equipment, maintenance trends, or capital planning support. Technology-enabled service providers help you understand your building as a managed asset.

The most revealing questions for service providers focus on outcomes and accountability:

If a provider can't give specific, data-backed answers to these questions, they're probably still operating in the old model.

The most profound change isn't technological—it's economic. Technology-enabled services finally align the interests of building owners and service providers in ways the traditional model never could.

Under the old system, service providers made more money when equipment failed or when maintenance took longer than expected. Building owners wanted reliable, efficient operations at predictable costs. These goals were fundamentally at odds.

Technology changes this dynamic by making value visible and quantifiable. When service providers can demonstrate avoided costs, energy savings, and extended equipment life, they can justify premium pricing based on results rather than hours.

"It's not more profitable for us, but it's the right thing to do if we want to work with our clients long term," Powell explains. "You also don't want to end up one day waking up to [companies like] Cushman Wakefield sending out Uber driver-style requests for an HVAC call, and you're just scrambling to respond first at the lowest price."

This shift has practical implications for contract structure and budgeting:

More predictable costs. Technology-enabled monitoring reduces surprise failures and emergency repairs. Building owners can budget more accurately when maintenance is driven by actual equipment conditions rather than arbitrary schedules.

Shared risk and reward. Advanced contracts might include provisions where service providers share in energy savings or receive bonuses for extended equipment life. This creates incentives for optimization rather than just maintenance.

Reduced administrative overhead. Automated monitoring and reporting reduce the management burden on building owners while providing better visibility into building performance.

The transformation also enables new service delivery models. Remote operations centers can monitor multiple buildings 24/7, dispatching technicians only when needed and arriving with specific diagnostic information and appropriate parts.

Despite the progress in data collection and analysis, a critical operational challenge prevents many service providers from fully embracing condition-based maintenance: their work order systems can't handle flexible, data-driven scheduling.

Most maintenance management software was built for the old model—scheduled tasks that happen regardless of need. These systems struggle with the dynamic decision-making that condition-based maintenance requires. When a building's data suggests that some equipment needs attention while other systems can wait, current software can't easily adjust schedules, bundle related work, or reallocate budget accordingly.

"The next biggest hurdle for making condition-based maintenance really work is [maintenance management] platforms," Powell explains. "There is no effective way for us to manage a flexible budget and bundle work orders and float PM tasks based on conditions of assets."

This creates a bottleneck for building owners. While the technology exists to identify what needs attention and when, translating those insights into efficient service delivery remains largely manual. Service providers need experienced personnel to make real-time decisions about work prioritization and resource allocation—a constraint that limits how quickly the industry can scale these approaches.

"You need someone who has many years of experience in the industry to do the right work order bundling and manage that budget for a customer," Powell notes. "So it's super clunky today."

For building owners, this means the full benefits of predictable, optimized maintenance remain partially unrealized. The ideal scenario—where building data seamlessly drives service decisions and budget allocation—requires better integration between monitoring platforms and operational workflows.

This limitation explains why the transformation remains in early stages and why companies like MacDonald-Miller represent exceptions rather than the rule.

Most service providers face significant barriers to adopting technology-enabled approaches: upfront software costs, the need for specialized staff, workflow system limitations, and uncertainty about return on investment.

But building owners don't have to wait for the entire industry to evolve. They can actively drive this transformation by changing how they approach service contract renewals and what they demand from providers.

Building owners ready to embrace technology-enabled services face a change management challenge as much as a procurement decision. The transition requires new ways of thinking about building operations, service relationships, and cost management—but it also represents an opportunity to gain competitive advantages while the majority of the market remains stuck in traditional models.

Start with your next renewal. Don't wait for contracts to expire—begin conversations early about shifting to outcome-based models. Give providers time to prepare new proposals that demonstrate value through data.

Define your outcomes. Be specific about what you want to achieve: energy reduction targets, comfort score improvements, reduced emergency repairs, extended equipment life. Vague goals produce vague results.

Invest in building data infrastructure. Technology-enabled services require connected building systems. If your building lacks adequate sensors or network connectivity, factor upgrade costs into your decision.

Plan for cultural change. Your facilities team may need training on new dashboards, reporting tools, and performance metrics. Budget time and resources for this transition.

Start with pilot programs. Consider testing technology-enabled services on a subset of buildings or systems before committing to organization-wide changes.

The transition isn't without risks. Early adopters may pay premium prices while the market matures. Technology integration can be complex, particularly in older buildings. And not all service providers claiming to offer tech-enabled services have the capabilities to deliver on their promises.

But the risks of not transitioning may be greater. As energy costs rise, sustainability mandates tighten, and building expectations increase, traditional service models become less viable. Building owners who wait may find themselves at a competitive disadvantage.

The transformation of building services represents a broader shift in how we think about building operations. Instead of treating mechanical systems as necessary expenses, forward-thinking owners are recognizing them as manageable assets that can drive competitive advantages.

"You're telling me you can't get rid of a service provider, because they dictate to you what needs to be done. They're the ones who know everything about the building," Turner challenges building owners. "You're not acting like you own this facility or that your mechanical systems are part of your asset that you actually own. You're acting like you're renting this from this service provider."

This mindset shift—from passive recipient to active partner—may be the most important outcome of technology-enabled services. When building owners have access to real-time performance data and clear accountability metrics, they can make informed decisions about maintenance priorities, capital investments, and operational strategies.

The technology exists. The service providers are evolving. The business models are emerging. What's missing is widespread adoption by building owners who understand their newfound leverage in these relationships.

Your next service contract renewal represents more than a routine procurement decision. It's an opportunity to fundamentally change how your building operates, how costs are managed, and how value is created.

The question isn't whether technology-enabled services will become the standard—it's whether you'll be an early adopter who shapes these relationships or a late follower who accepts whatever terms the market offers.

The choice, as they say, is yours. But the window for competitive advantage won't stay open forever.

Head over to Nexus Connect and see what’s new in the community. Don’t forget to check out the latest member-only events.

Go to Nexus ConnectJoin Nexus Pro and get full access including invite-only member gatherings, access to the community chatroom Nexus Connect, networking opportunities, and deep dive essays.

Sign Up

This is a great piece!

I agree.